This week, America welcomed its “new” first family back into the White House amidst competing flurries of optimism and angst. This post is not about them, however, but of another “first family”—our primordial parents Adam and Eve—whose original transgression in Paradise inaugurated the long human drama of disobedience, exile, and redemption. The iconic story from Genesis is essential to the spiritual framework of Dante’s Divine Comedy, shaping his conceptions of sin, knowledge, and freedom.

Genesis: Background and Themes

As the first book of the Hebrew Pentateuch, Genesis is traditionally attributed to Moses in the period following the Exodus from Egypt (~1400 BC) and represents the original meta-history of humanity.1

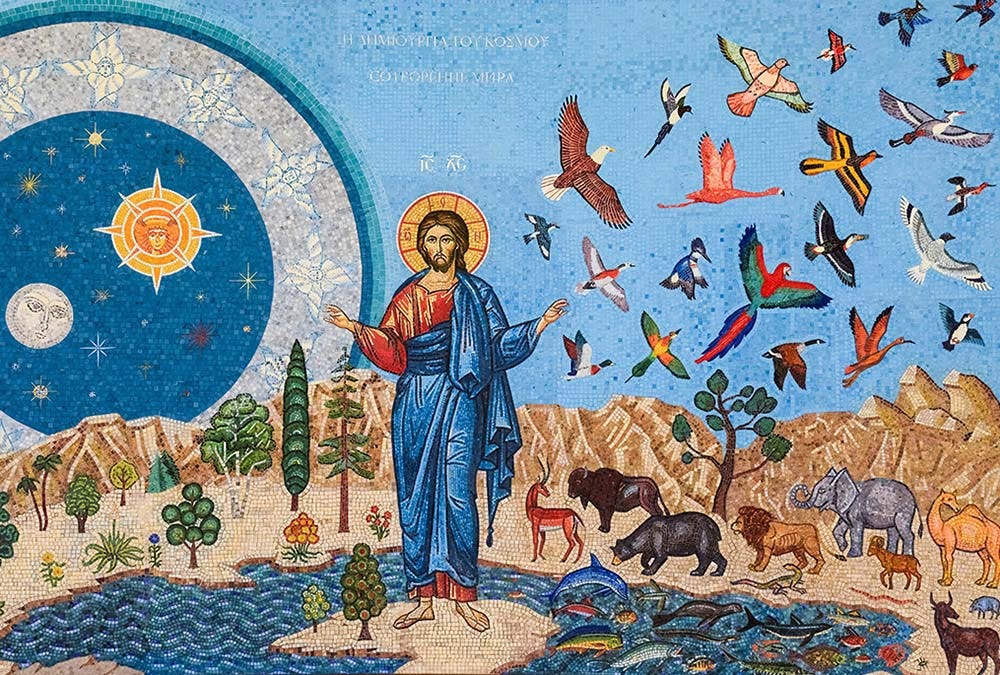

Genesis is a Greek word meaning “beginning,” as in coming into being, and is drawn from the opening verse of the text: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” Its major themes include:

The creation of the cosmos and life on earth

Human rebellion and punishment

The history of the earliest generations of men

God’s plan to restore fallen human nature through the line of Abraham

It is useful to divide Genesis into two main parts. Chapters 1-11 give a cosmological overview of creation, Adam and Eve’s sin and exile, Noah and the flood, and the Tower of Babel. Chapters 12-50 provide an anthropological narrative, detailing Abraham’s faith and covenant with God, the lives of his descendants, and Israel’s eventual sojourn in Egypt (which sets up the later narrative of the Exodus).

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters. And God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. Genesis 1:1-3

The Creation Account: A World Ex Nihilo (Genesis 1-2)

The origin story in the book of Genesis is among the most well-known passages in the Bible; possibly for this reason, its literary power tends to be lost on many. If you haven’t read the story in a while, I encourage you to do so here. Notice that it describes creation using a distinct “narrative couplet”—this means it tells the story twice, with a different literary emphasis each time.

I expect most educated readers are able to distinguish scientific from other types of writing, especially when dealing with ancient texts. Therefore, it should surprise no one that the opening chapters of Genesis ought not to be understood as opposing science, but as presenting religious and philosophical truths outside the material realm of secondary causes (more on that in a future post).

We’ve already seen how the tension between being and becoming has perplexed western philosophers since the Pre-Socratics. I believe that the Genesis creation story offers a tenable solution to this problem whereby mutable, contingent creatures derive their being from the eternal, uncreated God, who is Being Itself.

In the day that the Lord God made the earth and the heavens, when no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up…then the Lord God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul. (Genesis 2:4-5, 7)

Adam and Eve: Fall from Paradise (Genesis 2-4)

God forms Adam (Hebrew, man) from the dust of the earth to become, with his wife Eve (Hebrew, living), the first parents of all humanity. This biblical principle of our common parentage provides the foundation for human unity: "And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth" (Acts 17:26 ESV).

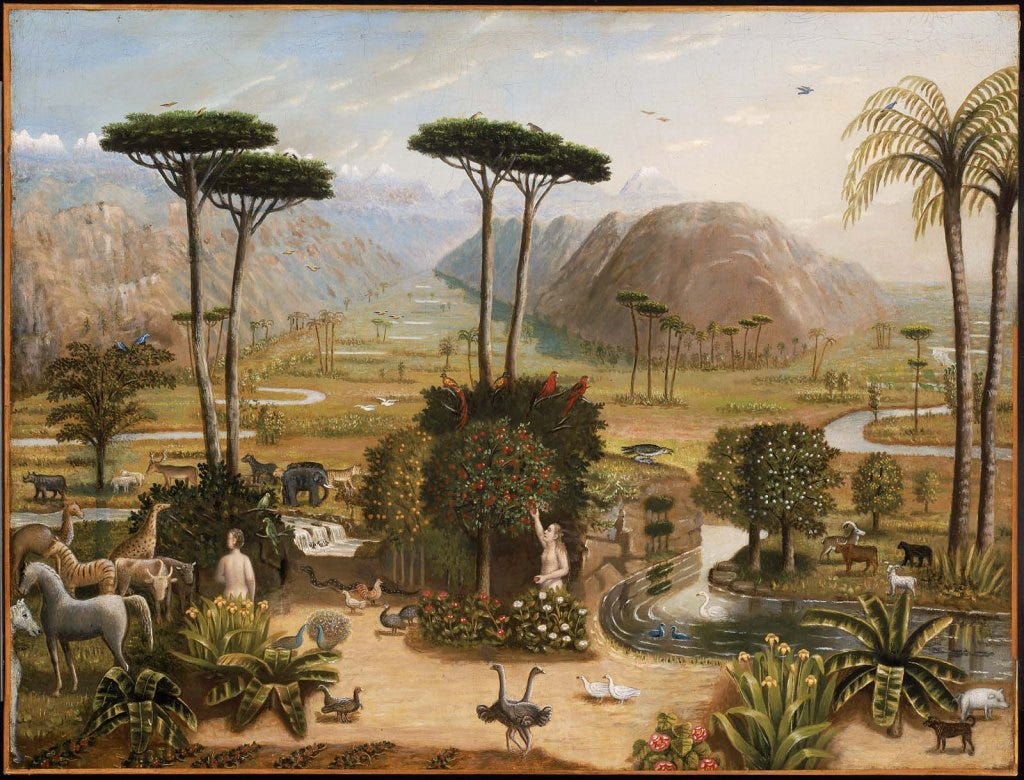

The couple’s first home is in Eden, a mysterious, even mythical place somewhere “in the east”, crowned with a paradisiacal garden atop a holy mountain.2 Despite various theories, no scholarly consensus exists as to the location of a historical Eden, though Dante locates his Paradise on top of Mt. Purgatory, at the antipodes of Jerusalem.

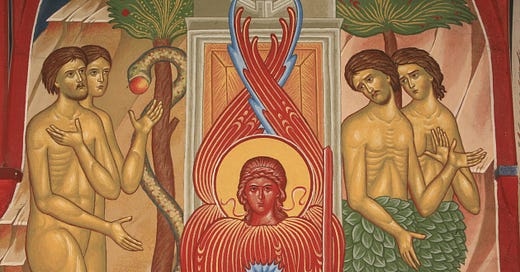

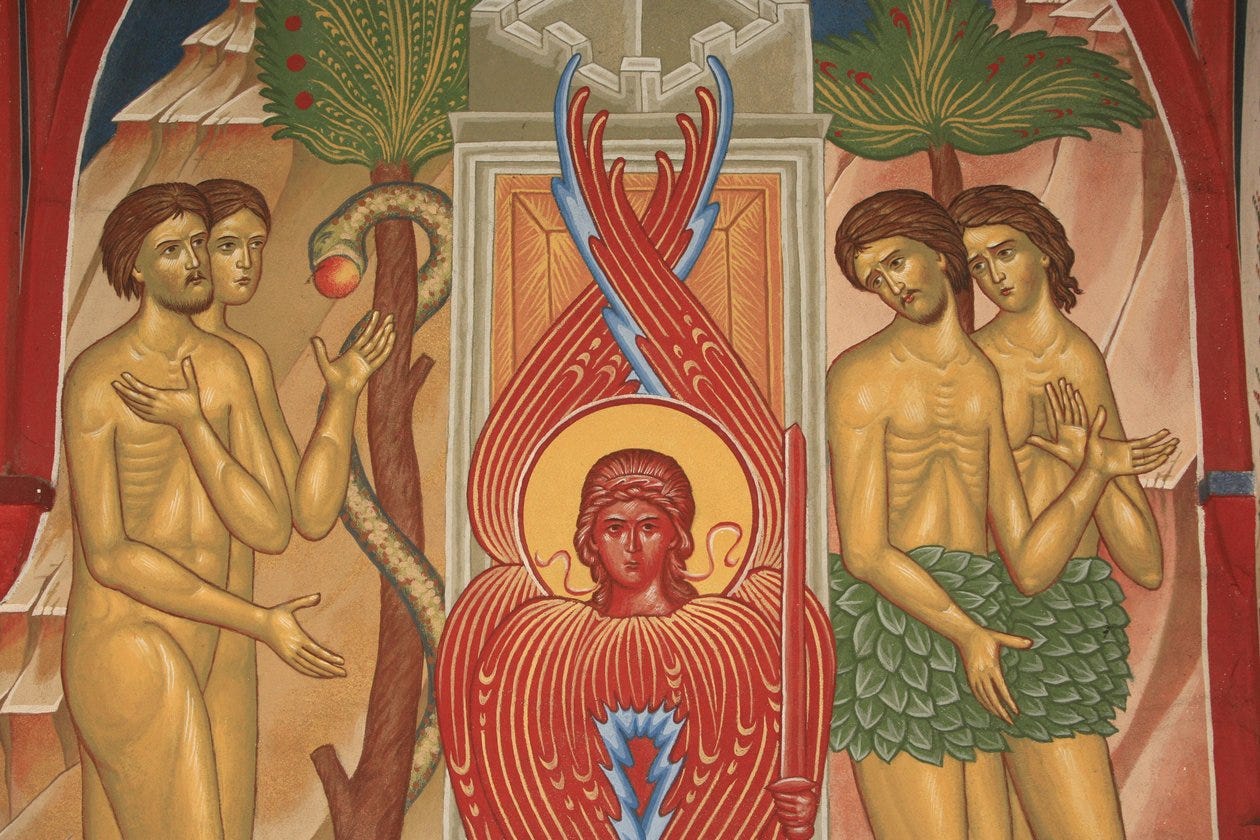

After making Adam and his wife caretakers of the garden, God gives them a paternal mandate that they may eat of any tree except the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil: “for in the day that you eat of it, you shall die” (Gen. 2:17). We all know the rest of the story: a cunning serpent convinces Eve that the fruit is safe to eat and will make her like the jealous God who withheld its goodness from her. She eats the fruit and gives some to her husband, making him complicit in her disobedience. They don’t die, of course, but “their eyes are opened” and upon discovering their nakedness, they sew a covering of fig leaves and hide themselves from God.

Faced with the couple’s transgression, God curses the serpent and pronounces pain, toil, and vexation upon the man and woman’s worldly labors and relationships. Then he casts them out of the garden, barring their re-entry with a flaming sword-bearing cherubim, lest they eat of the Tree of Life and incur immortality in their cursed state. They and their descendents will now live out their mortal lives as exiles in a hostile land.

The Tower of Babel: Pride and Power (Genesis 11:1-9)

The final story of the first part of Genesis tells of Noah’s descendent Nimrod, “a mighty hunter before the Lord,” who founded the future Babylon (Hebrew babel, confusion) where men first sought to “make a name for themselves” by building a great tower to reach the heavens. Babel is often seen as a cautionary tale against humanity’s overweening pride—men trying to be gods—and ends in God scattering the people and confusing their language. (As one of my favorite stories in Genesis, I’m saving the juicier details for a future bonus post!)

Dante’s Engagement with Genesis

The problem of original sin is a narrative thread running through all three cantos of the Divine Comedy. In the chart below, I’ve attempted to capture the significant references to Genesis, with particular emphasis on the Adam and Eve story, though my list may not be exhaustive. (Please let me know in the comments if I’ve missed any others.)

These passages suggest that humanity’s corruption and alienation from God are rooted in our first parents’ premature and disordered desire for knowledge. Dante understands their transgression as intellectual incontinence, a sin related to gluttony. Prof. Teodolinda Barolini (Columbia University) explains:

Dante himself does not treat the violation of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil by Adam and Eve as a fraudulent theft, but as a form of incontinence...Dante insists on the primal violation as a form of transgressive eating…by locating grafts from the tree of Eden on his terrace of gluttony in Purgatory.3

Modern readers may wonder why this seemingly minor violation incurred such catastrophic consequences for Adam and his progeny. Beatrice answers that by refusing to accept limitations on its will, human nature turned away “from its own path, from truth, from its own life” (Paradiso 7.38-39). Adam received his freedom from God and used it to repay Him with ingratitude and distrust, rupturing their original unity.

What Dante Teaches Us About Sin

To understand Dante’s vision in the Divine Comedy on his terms, we have to recover the traditional Christian sense of sin. Since the Enlightenment, modernity has increasingly rejected the idea of original sin as the ontological defect responsible for corruption and suffering in our world. Even in some Christian circles, it is popular nowadays to minimize the seriousness of sin by referring to it as “missing the mark” (Greek, hamartia), as though it were merely a matter of poor aim.

Dante would have found the social re-engineering of conscience preposterous. Yet it still leaves many asking, what is sin?

Thomas Aquinas defines sin as "nothing else than a bad human act” (Summa Theologiae I-II, 71, 6). Every act has an object, and sin is an “inordinate act” because it is not correctly or proportionately ordered toward a good end. Sin has two conditions: 1) it requires the consent of the will, i.e. is voluntary; 2) it violates or subverts some due measure of God’s eternal law and human reason. In The Divine Comedy: Tracing God’s Art, Marguerite Mills Chiarenza is emphatic on this point:

In order to read the Inferno properly, it is necessary to have an unequivocal understanding that sin is an act of the will…committed knowingly and intentionally.4

For Dante, disordered love underlies all our sinful actions. On the fourth terrace of Purgatory, Virgil explains that “love may choose an evil object or err through too much or too little vigor” (Paradiso 7.95-96). As long as it is directed toward the “First Good” (God) or toward secondary goods in their proper measure, love avoids error. “But when it twists toward evil, or attends to good with more or less care than it should,” it results in sin and deserves punishment. (Paradiso 7.100-101) .

Paradise Lost: Enduring Consequences of the Fall

The Fall has left humanity with the universal memory of a lost golden age, a hopeful vision of redemption, and a deep-seated instinct for self-sacrifice and atonement. The great demonic deception—you will become like God—disrupted every aspect of our original parents’ existence, and subsequently ours:

Relationship with God

Psychic harmony

The order of marriage and family life

Environmental stewardship

Mastery over our passions and thoughts

The experience of immortality

A perennial question persists: Will humanity learn to accept its creatureliness, or insist on fashioning itself according to its own designs? Both Genesis and Dante attest to the ancient wisdom that estrangement from God leads to alienation and exile, while trust in divine providence puts us on the right path to restoring our harmony and purpose.

As an Amazon affiliate, I receive a small commission on qualified purchases to support my work at no additional cost to the buyer.

Although we’ll occasionally encounter works whose authorship has come into question in modernity–especially by that tedious group of scholars, 19th century German theologians–I’ll generally refrain from such speculation, since our main interest is understanding the traditional views that influenced Dante.

While Genesis does not explicitly state that the garden is on top of a mountain, this traditional belief is supported by various interpretations of other scriptures, particularly Ezekiel 28:12-19: “...With an anointed guardian cherub I placed you; you were on the holy mountain of God; in the midst of the stones of fire you walked. You were blameless in your ways from the day you were created, till iniquity was found in you…” The venerable hymnographer Ephrem the Syrian (🕇 373 A.D.) wrote beautifully on this teaching.

Teodolinda Barolini, “Inferno 24: Metamorphosis (Ovid),” Digital Dante, last modified 2018, accessed January 18, 2025, https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-24/, paragraph 16.

Marguerite Chiarenza, ed., The Divine Comedy: Tracing God’s Art. (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1989) 29.

I’n no theologian, but I think there are several “senses of sin” across the schools of Christianity, rather than one universally adopted “tradition” — at least when it comes to original sin. They all agree on the “origin story”, but differ somewhat in its nature, transmission and effects. For example, I grew up in the Lutheran tradition in an area of Pennsylvania heavily populated with Amish and Mennonites, who are part of the Anabaptist tradition. Luther described original sin as a radical and pervasive corruption of human nature — not just inherited guilt, or a tendency to sin, but rather a complete distortion of being (“total depravity”). (That might explain why some Lutherans are strung pretty tight…) Anabaptists, while affirming original sin’s reality, view it as an inherited tendency to sin, rather than guilt (being held accountable for Adam and Eve’s Original Sin). They emphasize human responsibility for personal sin more than inherited guilt.

But I digress — back to Dante: I found it fascinating to think about his portrayal of Limbo and the interplay of original and personal sin with respect to the shades in Canto IV. Limbo has fallen out of fashion in the modern era, but it’s intriguing to see his deviation (poetic latitude) from contemporary portrayals. Thomas Aquinas viewed it as a place for those who died without baptism but were not guilty of personal sin. He divided it into two components: “Limbus Infantium” (Limbo of Infants) for unbaptized children, and “Limbus Patrum” (Limbo of Fathers). The kids’ table was eternal, but the adult table was a temporary abode. Aquinas argued that the death sentence for the unbaptized infants was a form of natural happiness, with freedom from suffering and enjoyment of the natural goods of human existence, such as peace and companionship, but without the supernatural joy of union with God. (The primary consequence of Original Sin). Quite a burden for the little ones. In Dante’s depiction, there’s no hope of a Harrowing or sanctifying grace for anyone. Therein lies the rub: you’re burdened by original sin yet without hope of rescue. No wonder everybody’s melancholy!

Amazing. You are able to really give a large picture of the Comedy. It’s a gift to be able to put together things that seems a part. I really appreciate the references to Genesis in the Comedy. I have difficulties to get together things too much apart. Thanks. Also, I appreciate that you underlined that sin is an act of will and not just a mishap. And this is not fiction, but theology. This helps to understand the behaviour of the Pilgrim and the Poet toward the damned. Italian scholars for long time, and still now someone, search for compassion where it would not be possible to find it, unless going against God’s will. Also the connection of sin with a misdirected desire/Love has so many implications in the text. I hope you will develop more. Thanks again. This is a very exciting journey.