Being and Becoming: A Prelude to Dante's Cosmos

What can Dante teach us about how to think about reality?

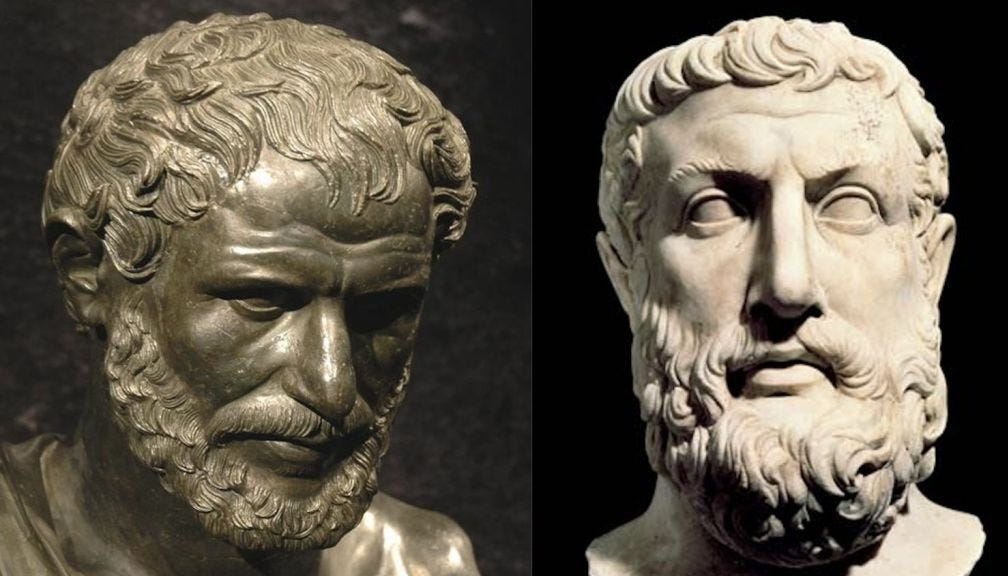

“There is one story left, one road: that ‘it is’. And on this road there are very many signs that being is uncreated and imperishable, whole, unique, unwavering, and complete.” ~ Parmenides

“Everything flows and nothing abides, everything gives way and nothing stays fixed…You cannot step twice into the same river, for other waters and yet others go ever flowing on.” ~ Heraclitus

As we prepare to explore Dante’s literary inspirations over the next several weeks, learning to decipher the grammar of his mythology and cosmic vision, I want to briefly review our progress. The guiding theme remains clear: Dante the Homo Viator, the “Everyman” of allegory, undertakes a journey of knowledge through matter (i.e., the cosmos) to a fulfillment of the soul beyond matter, which we call heaven—the realm of ultimate vision, consciousness, beatitude and being.

At the journey’s outset, we confront a universal truth: life’s complexities cause many folks—even Dante—to lose their way and wind up in a “dark wood”, a metaphorical landscape of error, isolation, and existential uncertainty. Such experiences bespeak our occasional alienation from truth, purpose, and authenticity. From this disorientation arises our need for a guide—a Virgil or a Beatrice, if you will—to help illuminate and accompany us on the path toward interior freedom, which is the ability to overcome the vices and obstacles that impede our purpose and happiness.

These are some of the larger themes that permeate Dante’s voyage through hell, purgatory, and heaven. As we accompany him on t his journey, we will learn not only to decipher the layered symbols and signposts of Dante’s poem but also to recognize such markers of meaning in our own lives. Dante’s allegory serves as a mirror, reflecting the universal struggle to reconcile life’s inescapable turbulence with the serene presence of mystery and goodness inherent in the world.

From Homer to Dante: Establishing the Cosmos

I’ve titled this series "From Homer to Dante" to emphasize the literary giants who frame the historical arc of the works we’ll examine. Before delving into Homer, though, I think it will be fruitful to try to reconstruct the broad outlines of Dante’s intellectual universe. (This, by the way, is an ongoing quest of my own intellectual life: to transcend the constraints of the modern imaginative vision by encountering bygone authors and their works within the context of their actual lived experiences and social milieu.) By understanding the philosophical, religious, and literary foundations of Dante’s world, we can better appreciate the characters, concepts, and themes he draws upon.

In this article , I will focus on the metaphysical question underpinning much of ancient Western cosmology: the conundrum of being and becoming. More to the point, how to reconcile eternal and unchanging reality with that which is transient and mutable? I admit that this sounds like a highly abstract problem of no practical value. The first time I encountered questions of being and becoming in Plato’s dialogues, I gathered vaguely that it was an ontological issue about eternal and passing things, but I didn’t understand why this distinction mattered. If you’re unsure, too, read on.

Being vs. Becoming: Ancient Perspectives

For the modern reader, the premise of anything as “unchanging” might seem dubious amidst the flux of daily life. Yet the ancients perceived enduring universal principles operating everywhere behind the veil of appearances. Obvious examples include unvarying mathematical truths, the stability of natural laws, and the predictable patterns of celestial movements. To ancient Greek thinkers, the heavens, especially, revealed a tableau of permanence beneath which our ephemeral human existence transpired.

Around the turn of the 5th century BC, the evident tension between permanence and mutability found articulation in the writings of two seminal Pre-Socratic philosophers: Parmenides and Heraclitus. Their opposing views ignited an important philosophical debate that echoes still through history.

Parmenides, belonging to the Eleatic School in Magna Graecia (southern Italy), upheld the primacy of being, necessity, and finitude. He defined reality as the unity of all existence, “that which transcends everything and is the highest of all beings”.1 For Parmenides, being stood outside of time, eternal and incorruptible. Sensory experiences of change were mere illusions; existence itself was a “finite ball of being,” ungenerated, indestructible, and complete.2

Heraclitus, conversely, championed the principle of becoming—the flux of existence. He is best known for his famous quote above about the impossibility of wading into the same river twice. Heraclitus saw unstable fire as the elemental substance, coinciding with the principles of transformation and strife. To Heraclitus, life’s essence lay in the perpetual cycle of creation and destruction, the interplay of opposites, a duality tending toward a polarized view of the universe.

Literary critic Hélène Tuzet encapsulated these worldviews as psychological archetypes in her 1965 study, Le Cosmos et l’Imagination.3 The Parmenidean thinker is an idealist drawn to the pathos of Unity. He desires simplicity in his assumptions and rigor in his doctrine. The Heraclitean type is a materialist embracing the pathos of Variety. She seeks liberation, dynamism, and polarity. Thus, the Parmenidean acknowledges a circumscribed existence while the Heraclitean demands absolute freedom. Such archetypes persist in contemporary cultural debates—tradition versus progress, unity versus diversity—illustrating the enduring conceptual categories we’ve inherited from these opposing philosophies.

Implications for Dante and Beyond

What relevance do these ancient debates hold for our study of Dante? I believe they reveal part of the metaphysical scaffolding that supports his imaginative vision. Dante seems always to be toying with the temporal and eternal, the finite and unlimited, whether it concerns themes of sin and penance, the nature of the soul, the great sea of being, or the source of authority behind papal and imperial power.

On a basic symbolic level, Dante invites us to explore our underlying assumptions about reality too. Charles Taylor calls this the social or “cosmic imaginary”;4 I’ve been using the term, imaginative vision.5 This holistic way of looking at the world derives from the largely unnoticed set of beliefs we absorb through the dominant cultural atmosphere. In itself, this kind of meta-narrative about our world is not a bad thing and is, in fact, a necessary part of meaning-making. To remain unaware of it, however, is to leave a large part of our intellectual formation unexamined.

In the next essay, we’ll explore Aristotle’s On the Heavens, and how he attempted to bridge the being-becoming divide through the duality of his cosmology, assigning permanence to the heavens and change to the earthly realm. This Aristotelian framework—expanded later by Ptolemy to become the orderly geocentric model of the cosmos that prevailed throughout the Middle Ages—would profoundly shape Dante’s cosmology scientifically, philosophically, and artistically.

Continuing our world-building, we’ll turn our attention after that to Ovid’s Metamorphoses to understand how its themes of creation and transformation influenced Dante’s depiction of the soul’s journey through the cosmos. Ultimately, these explorations probe a central question: Does meaning exist solely within the mind, or does it permeate matter and relationality? This line of inquiry will gradually take on form as we traverse the intricate exchange of mind and matter throughout Dante’s text—a dance of soul and body that has become increasingly challenging for modern thinkers since Descartes.

Thanks for joining me on this journey. Before I sign off, I’d like to leave you with this short video clip on Parmenides and Heraclitus from Philosophize This! Enjoy!

Jonathan Barnes, trans., Early Greek Philosophy, Second revised edition, Penguin Classics (London: Penguin Books, 2001), 85.

Ibid, 83.

Dennis Danielson, The Book Of The Cosmos: Imagining The Universe From Heraclitus To Hawking, Kindle edition. (Basic Books, 2001).

“[J]ust as the social imaginary consists of understandings which make sense of our social practices, so the ‘cosmic imaginary’ makes sense of the ways in which the surrounding world figures in our lives: the ways, for instance, that it figures in our religious images and practices, including explicit cosmological doctrines; in the stories we tell about other lands and other ages; in our ways of marking the seasons and the passage of time; in the place of ‘nature’ in our moral and/or aesthetic sensibility; and in our attempts to develop a ‘scientific’ cosmology, if any.” Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 323.

The term “imaginative” is not meant to imply that it is make-believe. Rather, it indicates the mind’s capacity to hold a wide range of images, beliefs, and impressions that are not necessarily present in our immediate environment.

Thanks again for exploring what il Sommo Poeta can teach us about how to think about reality. I think I understand what you’re “up to conceptually in this series”, and thus why the focus on Dante’s “world-building” is paramount at this early point, but I was struck by the fact that God isn’t mentioned once in this piece (unless references like the “serene presence of mystery” and “the eternal” are stand-ins). I’m not a particularly spiritual person, but it’s indisputable that the loom on which Dante’s cosmos was woven is Christianity. The Divine Comedy is a profound Christian vision; Pope Benedict said “Dante had no other purpose than to raise mortals from the state of misery, that is from the state of sin, and lead them to the state of happiness, that is of divine grace”. Dante was, as Charles Manley says, “saturated in Scripture,” and a “shepherd of the Christian imagination.” Yes, he had extraordinary (one might even say supernatural) perception about human experience and existence, from which we can reap great insights, but his work shouldn’t be distanced from its DNA. He uses the combination of the natural, human, and divine relationships to reality (and, of course, his personal calamity) to educate us.

Dante would have fervently agreed with the theologian Hans Boersma that Christ is the “central thread of the cosmic tapestry,” and the “eternal anchor for all of created existence.” Dante’s other threads may have included cosmology, history, topography, politics, philosophy, culture, and even revenge, but the purpose of weaving a unified tapestry was to set the stage for the Pilgrim’s redemptive journey and his hope in “a certain expectation of future glory"' (Paradiso, Canto XXV; 'glory' referring to the salvation of the soul). Dante constructed an imaginative, fantastically organized universe, as Michael Palma says, of “astonishing richness and texture.” It was the backdrop, as Jose Luis Borges says, for the poet to penetrate “the indecipherable province of God” and bring the pilgrim (on behalf of us all) face-to-face with the eminence “uncircumscribed and circumscribing all.” (Paradiso 14: 28-30). The Pilgrim’s initial “disorientation” may have prompted the need for guides, but in the deeply religious setting of the Divine Comedy, that “disorientation” was igniting the penultimate desire to see God face to face, and to quench the Pilgrim’s appetite for knowledge. His “dominant cultural atmosphere” was the Christian (Catholic) paradigm; Virgil (representing reason) and Beatrice (representing revelation) weren’t there primarily to help the pilgrim find “interior freedom” — they were there to guide him to “future glory.” As Saint Augustine said, “We have heard the fact: let us seek the mystery” — it was both an educational and spiritual journey.

Maybe C.S.Lewis can help us use tools like Dante’s elegant cosmos to derive personal meaning-making: “Every time you make a choice you are turning the central part of you, the part of you that chooses, into something a little different than it was before. And taking your life as a whole, with all your innumerable choices, all your life long you are slowly turning this central thing into a heavenly creature or a hellish creature: either into a creature that is in harmony with God, and with other creatures, and with itself, or else into one that is in a state of war and hatred with God, and with its fellow creatures, and with itself. To be the one kind of creature is heaven: that is, it is joy and peace and knowledge and power. To be the other means madness, horror, idiocy, rage, impotence, and eternal loneliness. Each of us at each moment is progressing to the one state of the other.”

Reverend Charles Brock said “The poem amazes by its array of learning, its penetrating and comprehensive analysis of contemporary problems, and its inventiveness of language and imagery.” Dante’s cosmos, then, has more than served its purpose as a map for Homo Viator’s search for “future glory.” I look forward to reading more about your perspectives on how it can be a useful map for overcoming “the vices and obstacles that impede our purpose and happiness.” Thanks again for revisiting the Pilgrim’s journey and being our pacesetter. Merry Christmas!

Perhaps Being and Becoming are two edges of the same sword; immanence and transcendence two separate aspects of the same Ultimate Reality. I feel there is something unchanging which underlies the obvious impermanence of our experience of existence, but allow I can't see it or point to it. I can only say "I feel this way", or "this makes sense to me; I agree with this, not so much with that...", which ultimately means I know nothing for certain. I appreciate the way you are approaching and presenting this study. Thanks for the challenge.