Lions and Leopards and Wolves, Oh My!

Exploring Vice and Meaning in Dante’s Dark Wood | Inferno Canto 1

Therefore a lion from the forest shall slay them, a wolf from the desert shall destroy them. A leopard is watching against their cities, everyone one who goes out to them shall be torn in pieces; because their transgressions are many. (Jeremiah 5:6 RSVCE)

Canto 1 of the Inferno plunges the reader immediately into a gloomy and mysterious world, a liminal place of shadows lurking between the discontentment of our mundane lives and the borderlands of the supernatural. In order to make sense of this world, we will need to keep three layers of human experience in the forefront of our minds:

The particularity of political and social life

The universality of the redemption story

The singularity of the soul’s personal journey towards God1

As a master poet, Dante weaves each of these layers seamlessly into his work, occasionally as distinct elements, but more often employing all of them at once in a particular image or scene. This is because Dante makes use of the multiple senses of meaning as he writes. In other words, the text of the Divine Comedy is polysemous—it operates at multiple levels of meaning simultaneously: literal, allegorical, moral, and anagogical. These meanings would have been familiar to any medieval scholar or reader of Dante’s time but require some explanation in our own. Dr. Phillip Mitchell of Dallas Baptist University describes the four levels in Dante’s poem:

The literal represents the most obvious reading.

The allegorical tends to understand the literal set of actions as being symbolic of certain other principles.

The moral draws ethical principles from the literal action.

The anagogical applies the principle to the final state of the believer[‘s soul].

I’ll use the famous scene in Canto 1 of the three beasts to demonstrate this point.

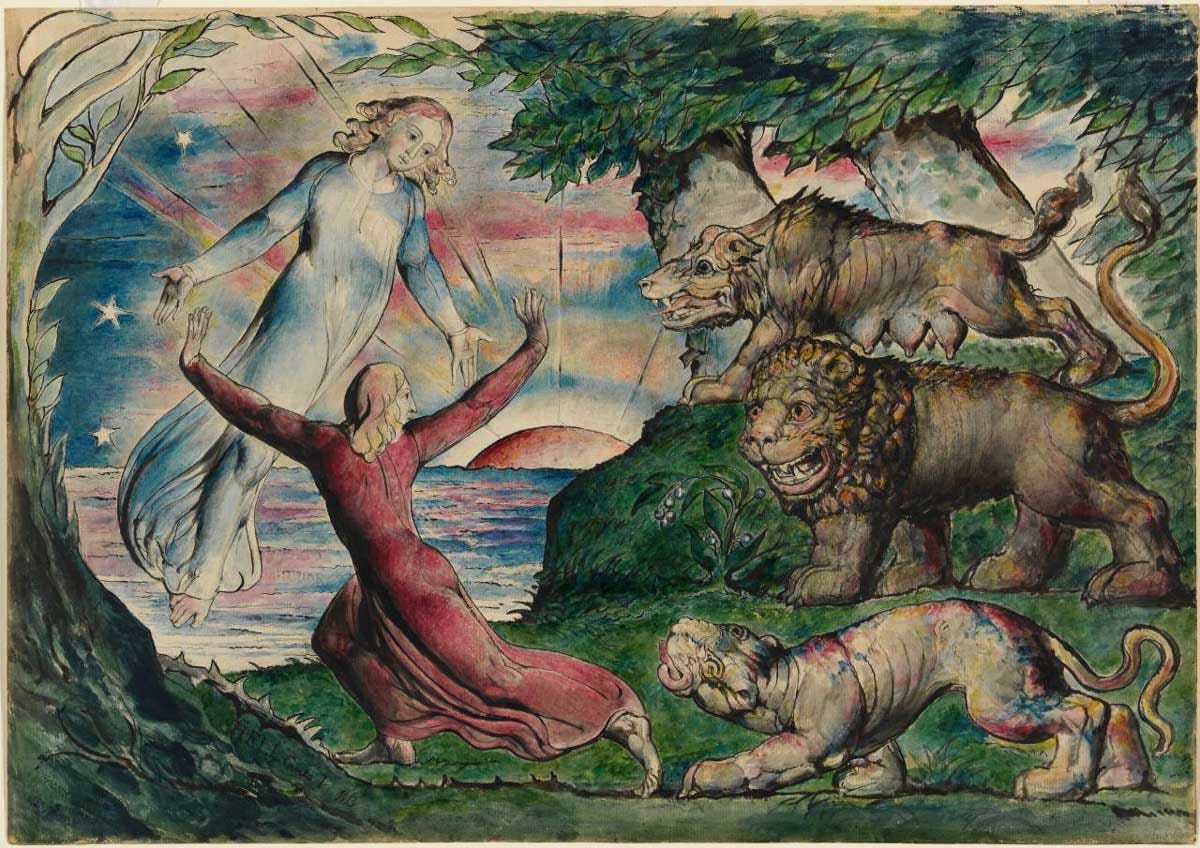

Three Beasts of Vice

When we left Dante the character in my last post, he had just awakened from a dull slumber, having lost his way and stumbled into a dark wood of error in the middle of his life. Not knowing the way out, Dante wanders through the night until finally emerging from the valley forest at the foot of a hill, which Dante hopes will leads him back to the true path2:

But when a mountain's foot I reach'd, where clos'd

The valley, that had pierc'd my heart with dread,

I look'd aloft, and saw his shoulders broad

Already vested with that planet's beam,

Who leads all wanderers safe through every way.

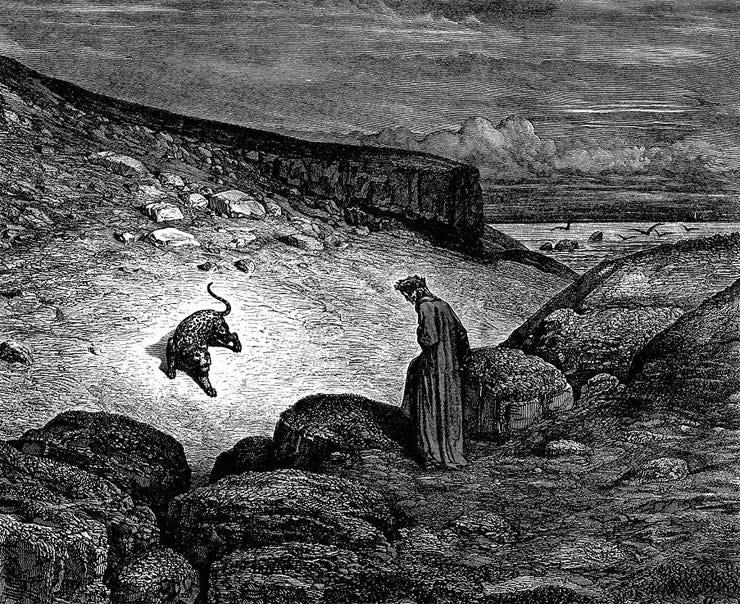

The sun (“that planet’s beam”) rising over the ridge rouses Dante’s courage and he swiftly makes to ascend the slope. As he nears the summit, however, his passage is blocked by three menacing beasts, beginning with a spotted leopard (or a “speckled panther” here in Cary’s translation)3:

Scarce the ascent

Began, when, lo! a panther, nimble, light,

And cover'd with a speckled skin, appear'd,

Nor, when it saw me, vanish'd, rather strove

To check my onward going; that ofttimes

With purpose to retrace my steps I turn'd.

After taking a moment to regain himself, Dante tries again to proceed but is routed by a lion, followed swiftly by a ravenous she-wolf. “She with such fear/ O'erwhelmed me, at the sight of her appall'd,/ That of the height all hope I lost.”4 Dante is forced to retreat in “heart-gripping anguish,” realizing he is powerless to overcome these beasts blocking his way to freedom.

How to Interpret Dante’s Symbolism

On the literal level, Dante is setting up the plot whereby his eponymous character will need to embark on a journey through the underworld with the assistance of a guide. We can continue to enjoy the unfolding story on this level, but most astute readers will want to fathom what Dante calls the “truth hidden beneath a beautiful fiction,” namely, the allegorical or symbolic meaning of the scene.5 By understanding what the beasts represent, we gain a threefold insight into the political machinations and social dysfunction of Dante’s world; the metaphysical conditions caused by sin universally; and Dante’s personal struggle with concupiscence.

Commentators widely agree that the symbol of the three beasts originates in the biblical verse from Jeremiah quoted above. Beyond that, though, scholars dispute the best interpretation. Nearly everyone understands the beasts as representing sin or vice—those which plagued Florentine society at large, and Dante to an extent—but they sometimes differ in their exegesis. The more traditional view (proposed by Dante’s son, Jacopo, who wrote the first commentary of the Commedia) reads the leopard, lion, and wolf as lust, pride, and avarice (greed), respectively. Later commentators will modify the list to incontinence, violence, and fraud, after the three main divisions of sin in Dante’s hell. But a problem with this interpretation, some scholars object, is its suggestion that Dante’s dominant sin is avarice or fraud, since it is the wolf that ultimately prevents his progress. An alternative reading given by C.H. Grandgent, reverses the order:

Inasmuch as the sins of Hell fall under the three heads, Incontinence, Violence, and Fraud, it is natural that the beasts should stand for corresponding practices: the ravening wolf is Incontinence of any kind, the raging lion is Violence, the swift and stealthy leopard is Fraud…We may understand, then, from the episode, that Dante could perhaps have overcome the graver sins of Fraud and Violence, but was unable, without heavenly aid to rid himself of some of the habits of Incontinence.6

Professor Marguerite Mills Chiarenza, author of The Divine Comedy: Tracing God’s Art, agrees with this interpretation: “We are not tempted, at least not usually, to do extremely corrupt things; we are tempted to do relatively innocent ones. This, I think, is why it is the wolf, the beast standing for the sins of weakness, who causes the failure of the pilgrim’s progress up the hill.”7

Aristotelian Morality

This interpretation, however, raises the question of why scholars classify the sin of incontinence as less grievous than fraud. Let me say a few words about the classical sense of morality. Beginning with Aristotle, incontinence (also called luxuria, lust) has been viewed as a disordered appetite or passion which causes a person’s will to give in to “the desire for a lesser good to the sacrifice of a greater one.”8 Essentially, the incontinent person fails to subordinate his appetites to reason, thereby inverting the proper governance of his soul. Aristotle considered incontinence more of a weakness than a moral failing. Likewise, the poet Dante assigns it to the upper level of hell, the least grievous station of the three aforementioned categories of sin.

The other two categories—violence (sometimes called wrath) and fraud (also called malice)—reflect an increasingly disordered and malicious will; but whereas violence still contains an element of involuntary passion, fraud is cold and calculating, originating entirely in the disordered use of reason. Thus it involves the complete corruption of a man’s rational nature, which Dante considers to be the worst crime. With this in mind, how should we reconcile the opposing interpretations of the vicious beasts?

As I’ve already alluded, the Divine Comedy is best read as an allegorical poem. But it is not a simple allegory as, for example, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, where there is a one-to-one correspondence between the symbol and the thing signified. Rather, “Dante insists that his allegories are not simple substitution codes…Instead, each of the four ‘senses’ of the text inheres in and evokes the other three simultaneously.”9 When confronted with conflicting or ambiguous interpretations, then, we should seek to clarify them through the four senses of meaning.

What is literally happening on the hill? Dante’s progress is blocked by three beasts of increasing levels of ferocity and hunger. The spotted leopard is described almost as innocent and playful, while the she-wolf is “…gaunt with the famished craving/ lodged ever in her horrible lean flank/ the ancient cause of many men’s enslaving.”10 What is it that most enslaves us? Recall that Dante brought us into his story when he began, “Midway along the journey of our life…” I think it is natural for each reader to incline to an understanding of Dante’s allegory that most closely corresponds to his own struggles on the moral plane. Are the “temptations of the flesh” just a passing youthful fancy? Perhaps the leopard embodies them for this reader. Or do they consume one’s soul with a ravenous and insatiable hunger? In this case, the she-wolf may be a more apt symbol, as I think was likely the case for the historical Dante.

Of course, my brief discussion here barely touches the surface of Dante’s symbology. I hope to develop it as a theme as we go long. At this stage of our journey with Dante, we sense that we are made for happiness even as we find that our progress is frequently blocked—occasionally by others but too often by circumstances of our own making. If we are honest, we may recognize the disordered priorities that occasionally (or habitually) govern our lives and rule our emotions and choices. But this is only the beginning of the story and remember, it’s a “comedy” after all. Better times are ahead…but not quite yet.

Having now established the theme of the first part of this journey, we will commence our exploration of Dante’s literary influences with the biblical and mythical stories of creation in my next post. Happy reading!

Reading Resources:

Dante’s Inferno Canto 1 - translation by Rev. H.F. Cary, free online resource by Owl Eyes.11

Jacopo Alighieri’s Commentary - the first commentary on the Divine Comedy by Dante’s son.

Jessica Hooten-Wilson, Reading for the Love of God - on reading with the 4 senses of meaning.

Richard Rohlin, Lecture 1 of “Dante’s Inferno: The Symbolic World Goes to Hell,” May 8, 2024, https://www.thesymbolicworld.com/.

Dante Alighieri, Inferno, trans. H.F. Cary, Owl Eyes Annotated Edition., 1314, accessed December 12, 2024, https://www.owleyes.org/text/dantes-inferno/read/canto-1#root-422360-1.

Vincent B. Leitch, ed., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 248.

Ibid.

Dante Alighieri, Il Convivio, II.1.

C.H. Grandgent, “Inferno 1.Nota,” Dartmouth Dante Project, last modified 1913, accessed December 12, 2024, https://dante.dartmouth.edu/search_view.php?doc=190951010000&cmd=gotoresult&arg1=0.

Marguerite Mills Chiarenza, The Divine Comedy: Tracing God’s Art (Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers, 1989), 34.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Alighieri, Inferno, I.72

You cite “three layers of human experience” as one of the ways to make sense of Dante’s journey. I’m going to hazard adding another — perhaps a more practical, yet hidden one — to help comprehend this encounter. What the animals may symbolize is, as you note, well-trodden ground. But a particular aspect of sense-making he employed when faced with the three beasts would, I suspect, escape a modern academic or reader. If experience is the chief architect of the brain, mine convinces me that Dante brought a very particular expertise with him — that of a hunter. I suspect Dante aficionados are now spitting up their espressos, but hear me out…

First, hunting was an elite pastime among men of Dante Alighieri's social class. It was a status symbol and a form of leisure that demonstrated prowess, bravery, diligence, patience, and cunning. It was viewed as practice for combat (Dante fought as a cavalryman at the Battle of Campaldino in 1289). It would not have been unusual for someone of his standing to participate in, or to at least to have been a familiar with hunting. Second, he employs hunting as a metaphor or simile in several instances in the Divine Comedy. For example, he uses the imagery of a hunter who has tracked down his prey to describe how the souls are pursued by their punishment; he compares himself to a hunter; he makes reference to God as a divine hunter, and he describes the movement of souls in heaven as being like the flight of birds when hunters approach. This hunting imagery would have been quite familiar to his contemporary audience.

Listen to Jose Ortega Y Gasset, the Spanish philosopher (and hunter), in his “Meditations on Hunting” (1943) recount what could well describe the Pilgrim’s dark woods rendezvous:

“In fact, the only man who truly thinks is the one who, when faced with a problem, instead of looking only straight ahead, toward what habit, tradition, the commonplace, and mental inertia would make one assume, keeps himself alert, ready to accept the fact that the solution might spring from the least foreseeable spot on the great rotundity of the horizon. Like the hunter in the absolute outside of the countryside, the philosopher is the alert man in the absolute inside of ideas, which are also an unconquerable and dangerous jungle. As problematic a task as hunting, meditation always runs the risk of returning empty-handed.”

From “Meditations” again: “…with maximum frequency, when a philosopher wanted to name the attitude in which he operated when musing, he compared himself with the hunter.” Many philosophers and poets (Plato, Aristotle, Xenephon, Chaucer, Shakespeare, etc.) found hunting a rich source for “musing.” Dante, I am convinced, was no exception.

A hunter — in Dante’s case, an unarmed hunter (and veteran) — would instantly revert to the ancient strands of his DNA and grasp and characterize the unique threat posed by each beast. The famous hunter Jim Corbett said “The word 'Terror' is so generally and universally used in connection with everyday trivial matters that it is apt to fail to convey, when intended to do so, its real meaning.” Only someone, I think, that has hunted or been in combat would fully appreciate the Paleolithic depth of the Pilgrim’s analysis. He is not panicked, if we understand panic to be “flight” driven by overwhelming fear in order to secure safety. He is, quite naturally, fearful — his “blood and pulse shudder”; but he “looks intently at the pass”; he let his “tired body rest awhile”; and “he had often to turn back again“ which certainly demonstrates both a diligence, and a subtle, calculated sense of the predators he faces. As Gasset says, “This is what hunting really is: a contest or confrontation between two systems of instincts…In the animal fear is permanent; it is his way of life, his occupation.” The Pilgrim is an alert man, but animals live in complete alertness, so they easily counter his steps (“he so impeded my ascent…she stalked me, step by step”). The Pilgrim, who lacks the honed instincts of the animal, substitutes determination; the poet, Dante, utilizes cunning to get his hunter out of his predicament (“…before my eyes there suddenly appeared…”) Convince me Canto 1 isn’t a hunter’s tale.