I’m a sucker for iconic first lines:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”—Dickens, Tale of Two Cities

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”—

Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

“I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I think my liver is

diseased.”—Dostoyevsky, Notes From Underground

But for my all-time favorite first lines, it’s a tie between Homer’s Iliad (“Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles…”) and Dante’s Inferno:

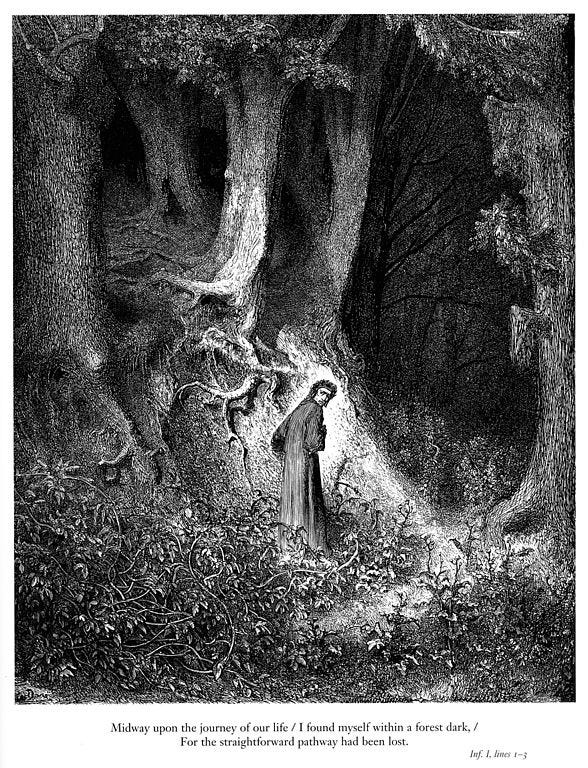

Midway along the journey of our life

I woke to find myself in a dark wood,

for I had wandered off from the straight path.1

Thus begins Dante’s tale2 of his journey to the underworld, a journey whose ultimate destination is heaven, not hell. Like many a classic story it begins in media res—in the middle of things. Out of a dull slumber, Dante suddenly comes to himself in a wild and unfamiliar place. Where had he been going and how did he happen upon this dark forest? We aren’t told. Indeed, it seems as if he doesn’t know either: “How I entered there I cannot truly say, I had become so sleepy at the moment when I first strayed, leaving the path of truth.”3 We do know, however, that Dante has stumbled into this predicament during midlife. The year is 1300 and Dante is precisely thirty five years old.

If we imagine a typical life in the Middle Ages spanning a 70 year arc, then Dante’s tale begins at its apex, the center and (what should have been) highest point of his earthly pilgrimage. In fact, the historical Dante had by this time attained the zenith of his political career, namely, election to the office of Prior, the highest government position in his prosperous city-state of Florence.4 This achievement, however, occurred amidst the escalating violence and intrigue that plagued Italian politics throughout the calamitous fourteenth century. What should have been the crowning of his career was soon followed by his greatest trial—political exile that would last the rest of his life.

Stuck in the Middle

So as this poem commences, we find Dante floundering in what we would call today a “midlife crisis.” Nor should we overlook the subtle suggestion that he’s addressing us, too, in this predicament when he says, “midway along the journey of our life...” Who doesn’t sympathize with Dante’s bewilderment upon finding that, far from solidifying his happiness, his momentary success has merely triggered an impending downturn of fortune? Likewise, who hasn’t looked back on his or her own life with the passing of time and discovered that they don’t recognize it anymore? I’m reminded of another poet, Billy Collins, who writes in his poem “Aristotle”:

This is the middle.

Things have had time to get complicated,

messy, really. Nothing is simple anymore.

Cities have sprouted up along the rivers

teeming with people at cross-purposes—

a million schemes, a million wild looks.5

Let us call this messy, complicated, unfamiliar terrain the Dark Wood of Error, conceiving error as all that promises—but can’t finally deliver—happiness. No one pursues an idea, goal, or philosophy with the intent of being deceived. Yet how many times have we been disappointed by our efforts to obtain some good we expected to secure our happiness—be it any of the multifarious forms of honor, wealth, power, or pleasure? Dante had at various times staked his happiness in courtly love, the pursuit of art and knowledge, and political life. But all values falsely elevated to an absolute goal lead to this Dark Wood in the end, where what awaits us is not happiness but anxiety, fear, and isolation.

Which brings us to ask: what does it really mean to be lost?

There are generally two ways of being lost (or disoriented) in a geographical sense: 1) knowing where you are, but not where you’re going; or 2) knowing where you’re trying to go, but not where you are.6 These ways of being physically lost provide a useful metaphor for reflecting on what it means to be existentially lost. Knowing where I am but not where I’m going is a problem of purpose, or what the ancient Greeks called telos, the end towards which all our actions point. On the other hand, knowing where I want to go but not recognizing where I am is a problem of authenticity, of “authoring” a life intended to reflect the goals and values I’ve set for myself. How do I know if I am currently stranded in one of these predicaments? Here are a few questions for self-reflection:

Questions of Purpose:

Do I have a clear, compelling, and particular vision for my life?

Do I feel that my life is advancing in the direction of my goals?

Do I struggle to say “no” to commitments that I’m not really invested in?

Do I experience anxiety about the future?

Questions of Authenticity:

Does my life ever feel “unreal” or disconnected from my purpose?

Am I living in imitation or envy of other people’s lives or achievements?

Are my dearest values and commitments manifested in my daily actions and behaviors?

Do my thoughts dwell on past regrets?

What shall we say of our friend Dante at the outset of this journey? Do you think he is struggling with purpose or authenticity? Leave your comments below. Next week, we’ll discover what happens when Dante decides to flee from the dark forest and make his way to higher ground.

Reading:

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Inferno, trans. Mark Musa (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984), 67.

Critics of the The Divine Comedy traditionally differentiate between “Dante the poet” and “Dante the pilgrim” or character in the poem. Since my purpose here is largely one of self-reflection and not literary criticism, I will often use his name interchangeably.

Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Inferno, 67.

Marguerite Mills Chiarenza, The Divine Comedy: Tracing God’s Art (Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers, 1989).

Billy Collins, “Aristotle” from Picnic, Lightning. Copyright © 1998 by Billy Collins. Accessed digitally at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46706/aristotle

We might propose a third category, in which someone neither knows where he is or where he is going, but in that case identifying his position doesn’t matter since any place will do. To be “lost” assumes at least one point of reference; having no point of reference is to be “pointless”.

I think I am in a dark forest. I brought matches, though.

Of wonderful opening lines, one cannot bypass The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: “There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb and he almost deserved it.”