Upon That Day We Read No More

Francesca da Rimini and courtly love/lust: a rare translation of Inferno Canto V by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Unlock the timeless wisdom of the West—join The Occidental Tourist for weekly free insights into the books and ideas that shaped history, culture, and the human spirit!

I’m currently working on my next series of posts exploring Homer’s role in shaping Dante’s literary vision. As Valentine’s Day approaches, however, I thought it would be fun to look at one of the Inferno’s most memorable characters, the love-struck Francesca da Rimini. She took up an ill-fated affair with her husband’s brother, Paolo, and wound up in Dante’s hell. I’m including the text of a rare translation of Francesca’s famous scene by another Dante you should know, surname of Rossetti: the 19th century English poet and painter (and brother of Christina Rossetti) who helped found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Enjoy!

Inferno Canto V: The Circle of Lust

Francesca da Rimini appears in Inferno Canto V as one of the damned souls in the circle of the Lustful. In real life, she was the daughter of Guido Vecchio da Polenta, lord of Ravenna. Around 1275, she was married for political reasons to Gianciotto Malatesta, the daring but lame son of Malatesta da Verrucchio, lord of Rimini. After her apparently loveless marriage, she became romantically involved with Gianciotto’s younger brother, Paolo Malatesta—and was murdered by Gianciotto when he discovered the pair in an adulterous embrace.

Dante's portrayal of Francesca is one of the most compelling scenes in the Inferno, an example of high performance art which throws our ethical distinctions and sympathies into a moral tug-of-war. Francesca recounts her downfall with elegance and sorrow, describing how she and Paolo were reading the courtly romance of Lancelot and Guinevere when, mirroring the characters’ passion, they succumbed to their desire for each other. As Lancelot kissed Guinevere, Paolo seized that moment to lock lips with Francesca—at which she remarks pointedly, “Upon that day we read no more.”1

Nursing her self-pity, Francesca laments that "Love has conducted us unto one death,"2 reflecting the medieval courtly tradition that viewed romantic love as an irresistible force. The pilgrim Dante is moved to sympathy for her tragedy. “Thine agonies, Francesca/ Sad and compassionate to weeping make me.”3 Dante the poet, however, artfully reveals the subtle manipulation of Francesca’s narrative: though she speaks poignantly of their fate, she never actually names Paolo as her lover and accomplice, referring to him only impersonally (“he whom nought can sever from me now”), with a wounded tone of resentment.

Transcending the moralistic sentiments of his day, Dante treats the sin of lust (lussuria) with limited attention to its carnality, emphasizing instead its subjugation of reason to stormy desires.4 Francesca’s punishment, therefore, reflects her sin: she and Paolo are eternally condemned to be buffeted about in a dark storm, symbolizing the uncontrolled passion of their counterfeit love. Moved by her story, Dante the pilgrim collapses under a surge of pity at the end of Canto V—the first of his early struggles to reconcile compassion with divine justice. As his journey progresses, however, Dante will learn to recognize sin as the unequivocal perversion of reason and truth, baldly incompatible with the pure vision of God he is pursuing.

“Francesca da Rimini” - a translation by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

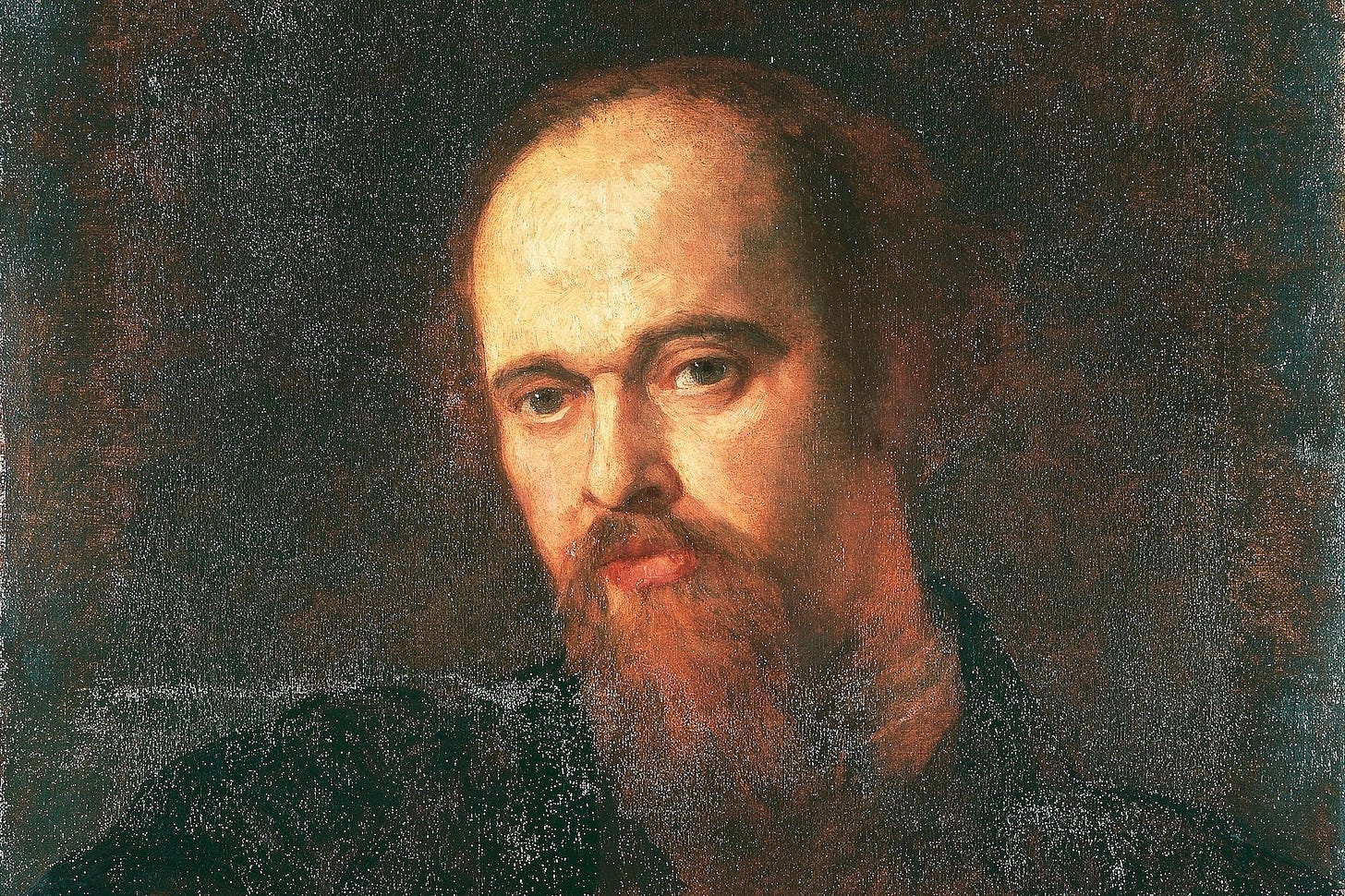

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was an English poet and painter who lived from 1828-1882. The son of an Italian Dante scholar and émigré, Rossetti devoted much of his artistic work during the 1850’s to his literary namesake and other medieval themes. He completed a translation of Dante Alighieri's La Vita Nuova in 1861. The following is his translation of the passage we’ve been discussing in Inferno Canto V, from Poems by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (circa 1870).5

FRANCESCA DA RIMINI

(Dante.)

When I made answer, I began : ‘Alas!

How many sweet thoughts and how much desire

Led these two onward to the dolorous pass!’

Then turned to them, as who would fain inquire,

And said: ‘Francesca, these thine agonies

Wring tears for pity and grief that they inspire:

But tell me,—in the season of sweet sighs,

When and what way did Love instruct you so

That he in your vague longings made you wise?’

Then she to me: ‘There is no greater woe

Than the remembrance brings of happy days

In Misery; and this thy guide doth know.

But if the first beginnings to retrace

Of our sad love can yield thee solace here,

So will I be as one that weeps and says.

One day we read, for pastime and sweet cheer,

Of Lancelot, how he found Love tyrannous:

We were alone and without any fear.

Our eyes were drawn together, reading thus,

Full oft, and still our cheeks would pale and glow;

But one sole point it was that conquered us.

For when we read of that great lover, how

He kissed the smile which he had longed to win,—

Then he whom nought can sever from me now

For ever, kissed my mouth, all quivering.

A Galahalt was the book, and he that writ:

Upon that day we read no more therein.’

At the tale told, while one soul uttered it,

The other wept: a pang so pitiable

That I was seized, like death, in swooning-fit,

And even as a dead body falls, I fell.

This great line also famously alludes to St. Augustine’s conversion scene in the Confessions, in which, having been finally convinced of the truth of the Scriptures he had been reading, he writes, “I had no wish to read further, nor was there need.” Confessions, 8.12.29.

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Inferno 5.106 (Longfellow translation)

Ibid, 5.116-117.

Barolini, Teodolinda. “Inferno 5: What’s Love Got to Do with It? Love and Free Will.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-5/

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. Poems. (New York: A.L. Burt Company, n.d.), 143-144.

As an Amazon affiliate, I may receive a small commission on any qualified purchases made through links in this post…at no added cost to the buyer.

Just a thought from my notes about canto 5, before going to sleep:

The fact that Dante encounter as first individual sinner a woman gives us a hint about his consistence with the Bible. A woman was the origin of damnation (EVE) and a woman was the carrier of salvation (MARY).

There are no hidden derogatory thoughts. As a matter of fact, the image of woman that the Poet is building in the whole poem is the true image that Christianity offers in the Gospel: a positive image.

Today, we live in a world where the women are not considerate inferior and are not subordinate to different laws than men...because of the Gospel! The story of the mother of God has permeated our Western culture for 2000 years and slowly, but continuously, has moved women from the lowest position in society to equality, both giving strength to the women and opening the heart of the men in power to pass good laws to protect them.

The moment you take away Christianity, women are removed from the image of “carriers of salvation” (as in Beatrice and Mary) and go back to Eve, “carrier of sin”, or even worse, as visible in countries where Christianity has not been the base of the general cultural choices.

Moreover, the moment countries reject Christianity and go toward a clear atheism, women are pushed to abandon the position of fundamental elements for the construction of the future of humanity, through birth, education and protection of children, in order to attain apparent power and freedom through work and activities that in reality are conducive to a path of social instability and even depopulation.

I don’t know any country where culture is based NOT on Christianity, that have a condition of freedom and equality for women as in the Christian so-called Western World.

DANTE, IN THIS IDEA OF WOMEN, IS NOT AN EXCEPTION, BUT A NORMAL CHRISTIAN THAT UNDERSTOOD THE GOSPEL AS MANY OTHER CHRISTIANS THAT HELPED BUILT OUR SOCIETY.

I think about this: the first sinner we meet personally is a woman, Francesca, with a silent and crying man, and the last person we will meet at the end of Paradiso is a woman, Mother Mary, more than a saint, addressed by Saint Bernard with a petition in favor of Dante’s salvation.

Do you see any connection with the relation between Eve and Mary? What else could give more importance to women for a Christian, but indicate them as pillars of a path of conversion, exalting them all in the final figure of Mary.

Wow!