Unlock the timeless wisdom of the West—join The Occidental Tourist for weekly free insights into the books and ideas that have shaped history, culture, and the human spirit!

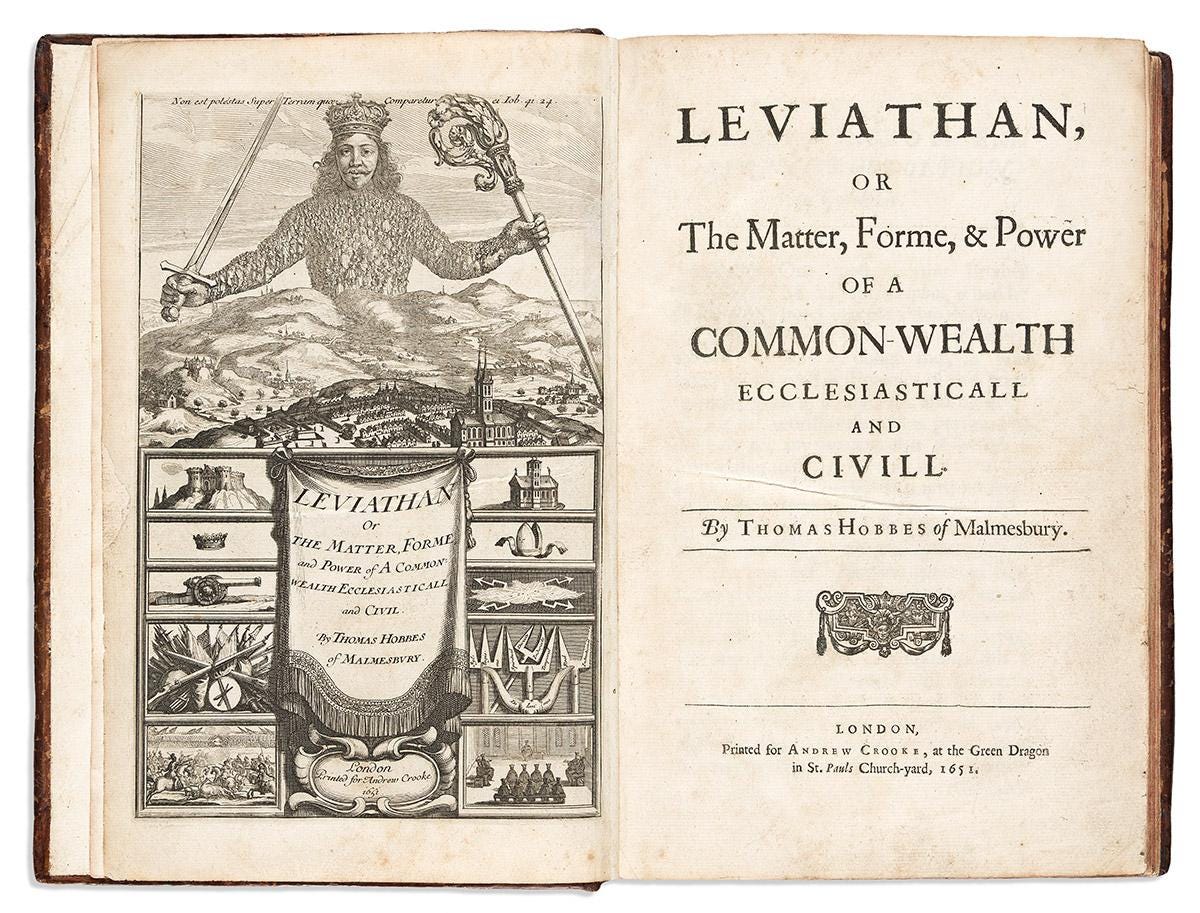

My Great Books reading club met this past Wednesday to discuss Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes’ 17th century treatise on man, politics, and power. This is the work that brought him into disrepute with Royalists and Parliamentarians alike during the tumultuous age of Oliver Cromwell, but also ensured secured his lasting place in the history of philosophy. You can access my study guide here:

Leviathan begins with an exploration of human psychology, language, and social behaviors before mounting a pessimistic argument for the political necessity of the social contract. Hobbes describes an account of reality defined by “a condition of war of every one against every one.”1 Only by entering into a covenant with an absolute sovereign—invested with both legislative and protective authority—can human beings ensure mutual peace and security. The cost of this arrangement, however, is the forfeiture of certain rights and freedoms.

Readers today may be drawn to, or repulsed by, Hobbes’ hard-nosed political realism. But I think there’s something more insidious at work in Leviathan—his metaphysical nominalism.

Hobbes bluntly denied the existence of universal forms, claiming that only the names we assign to things are universal, while the things themselves are “every one of them individual and singular.”2 In other words, terms like “man” or “tree” refer not to shared essences, but merely to verbal conventions that group isolated particulars. Each man or tree, in Hobbes’ view, is an atomistic being, essentially unrelated to every other.

Compound nominalism with empiricism—the theory that all knowledge is derived from sense experience, which Hobbes also affirmed—and centuries later you arrive at what journalist Mary Harrington describes as “an anthropology that rejects human meaning and human purpose, for one that sees only cause, and effect, and materiality to be engineered.”

Truth Seeking and Human Telos

Harrington’s insights about the collision of truth, technology, and human relationships reveal just how calamitous the adoption of bad metaphysics can be. “The most destructive progressive policies today,” she writes, “have their grounding in the idea that there’s no truth, and no normative nature to anything – even, or especially, people.”

“What is truth?” a Roman governor once famously inquired of his prisoner. Ask a classically-trained metaphysician and you’ll hear something like: truth is the agreement of an object with its corresponding idea in the intellect. This definition presumes a normative relationship between thought and being—a shared ontology.3

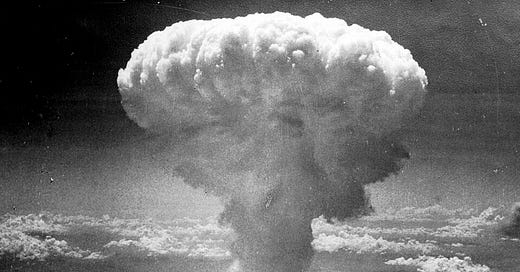

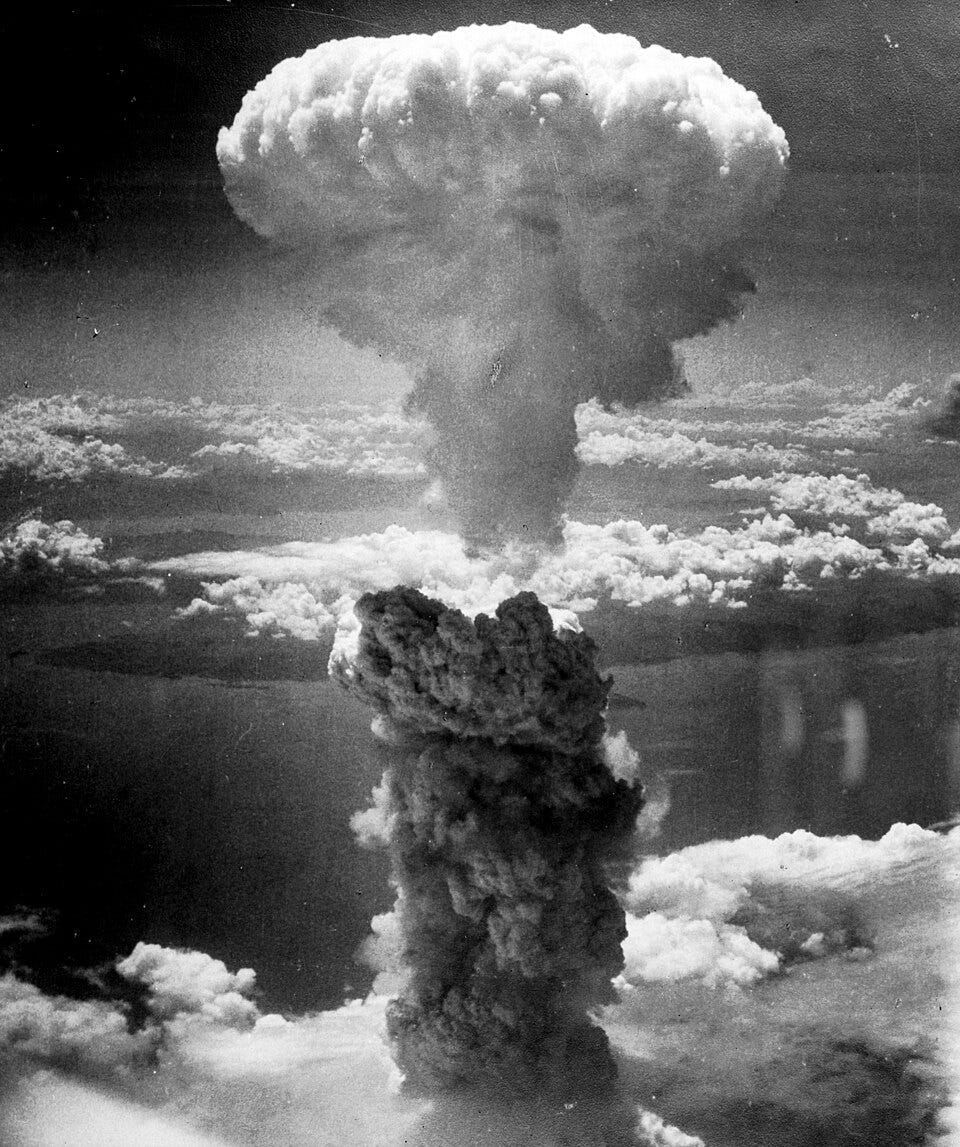

This is exactly what Hobbes denies, along with his post-modern successors, who—as Harringtong notes—have revolted against human nature and telos (purpose) in order to engineer their vision of reality governed exclusively by material cause and effect. Harrington concedes that this ideological shift has enabled “potent discoveries” in science and technology, but it has also yielded catastrophic outcomes like the atomic bomb. More broadly,

…when you scale this kind of applied technicity up to the level of societies, and the governments that order them, this blind spot in the shape of meaning and relationships begins to look like many of the challenges we are discussing…The collapse in family formation; the bleeding away of rightly ordered sexuality into hedonism or apathy; the inability to grasp why mass migration is widely unpopular and highly volatile at scale; the disintegration of religious faith.

A Tyranny of the Univocal Imagination

What most unsettles me about Hobbes and his intellectual heirs is the hidden contradiction at the heart of their nominalist worldview. It doesn’t quite emerge in Harrington’s post, focused as she is on the downstream effects of human and social re-engineering. It has to do with the kind of imagination they apply to reality, and how their ideas gain transmission and authority.

As we have seen, Hobbes roundly rejects Aristotle’s metaphysics—things like form, incorporeal substances, and final causes—insisting that reality relates only to univocal terms, not to essences. Yet at the same time, he attempts to impose a tyrannical uniformity on reality through the lens of his “master idea,” the belief that all men are in a state of war with each other and perpetually competing for power.

Though Hobbes denies objective categories such as good, evil, justice, and injustice, relegating them to expressions of individual appetite or aversion, he nonetheless posits a universal equivalence among human beings. But this equality is not grounded in dignity or nature; it is merely a rough parity of strength and cunning that leads inevitably to violent conflict. In this way, Hobbes prefigures what Harrington calls “the central postmodern claim”: There is no truth, only power.

Author William Lynch, S.J., describes such philosophical incoherence as the result of what he calls the “univocal imagination.” In Christ and Apollo: The Dimensions of the Literary Imagination, Lynch writes,

[T]he univocal mind often poses as the exclusive organizer and interpreter of a highly concrete, pluralistic, and individuated world. What was a legitimate process as it rose out of this world to create its own forms of sameness…now becomes not only illegitimate but dangerous as well. Now it not merely isolates and externalizes; its whole temptation is to reduce everything, like and unlike, to a flat community of sameness—all in the name of an intelligibility and type of order that does not and cannot belong to the real world.4 (Emphasis mine.)

This, perhaps, is the ultimate irony of Leviathan: a project that denies transcendent order in order to enforce a totalizing one of its own design. In fleeing metaphysical reality, Hobbes helped pave the way for modernity’s most misguided illusion—that science and politics can liberate us from our own limited and defined natures.

Like many websites, The Occidental Tourist uses affiliate links, which allows us to earn a small commission on any qualified purchases, at no additional cost to the buyer.

Thomas Hobbes, “Leviathan,” in Machiavelli | Hobbes, trans. W. K. Marriott, Second Edition., vol. 21, 60 vols., Great Books of the Western World (Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 2003), 86.

Ibid, 55.

I’m speaking specifically of ontological truth. In the case of logical truth, the relationship between intellect and thing is reversed: the thing is prior, and the idea posterior. Cf. Celestine N. Bittle, The Domain of Being: Ontology (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1938).

William F. Lynch and Glenn C. Arbery, Christ and Apollo: The Dimensions of the Literary Imagination (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2004) 159-160.

Great summary! The political problem with Hobbes leads directly into the spiritual problem with Hobbes, and back. The replacement of the Aristotle/Aquinas idea of Natural Law with his version results in a very inhumane picture of humanity and all the attending misery, unless of course you happen to be the one Sovereign. One can see how this thought leads to Marx/Stalin/Mao/Hitler, Atheism, war, xenophobia, unlimited State power, and all the other assorted degradations of humanity.

I think David Bentley Hart's recently published 'All Things Are Full of Gods' is very relevant to this post.