Plutarch's Lives: Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius

The Lawgiver and The King

Hello, dear readers. I’ve been away for a graduation and family reunion but I’m back and eager to share this latest reflection. The milestones that mark a young person’s life are a fitting backdrop against which to reflect on the first of Plutarch’s “Parallel Lives”—the lawgiver Lycurgus of Sparta vs. King Numa Pompilius of Rome. In Plutarch’s paired biographies, we see how two very different rulers organized and provided for political and domestic life. How do their methods strike you today?

The Greek writer Plutarch was born in the 1st century AD and died in 119. In his 70 or so years, he amassed a large collection of works, of which his “Parallel Lives” are the most acclaimed. We might say that Plutarch is to biography what Herodotus is to history; by which I mean that he is the first writer of distinction to introduce his work as a recognized form. Still, it would be unfair to compare Plutarch’s stories of ancient Greeks and Romans to the biographical form we think of today. We’d do well to remember the advice of Arthur Hugh Clough, editor of the Modern Library edition of Plutarch’s Lives:

In reading Plutarch, the following points should be remembered. He is a moralist rather than an historian. His interest is less for politics and the changes of empires, and much more for personal character and individual actions and motives to action; duty performed and rewarded; arrogance chastised, hasty anger corrected; humanity, fair dealing, and generosity triumphing in the visible, or relying on the invisible world.1

With this in mind, let us turn now to Plutarch’s first ancient pairing—Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius.

Lycurgus - Equality and duty

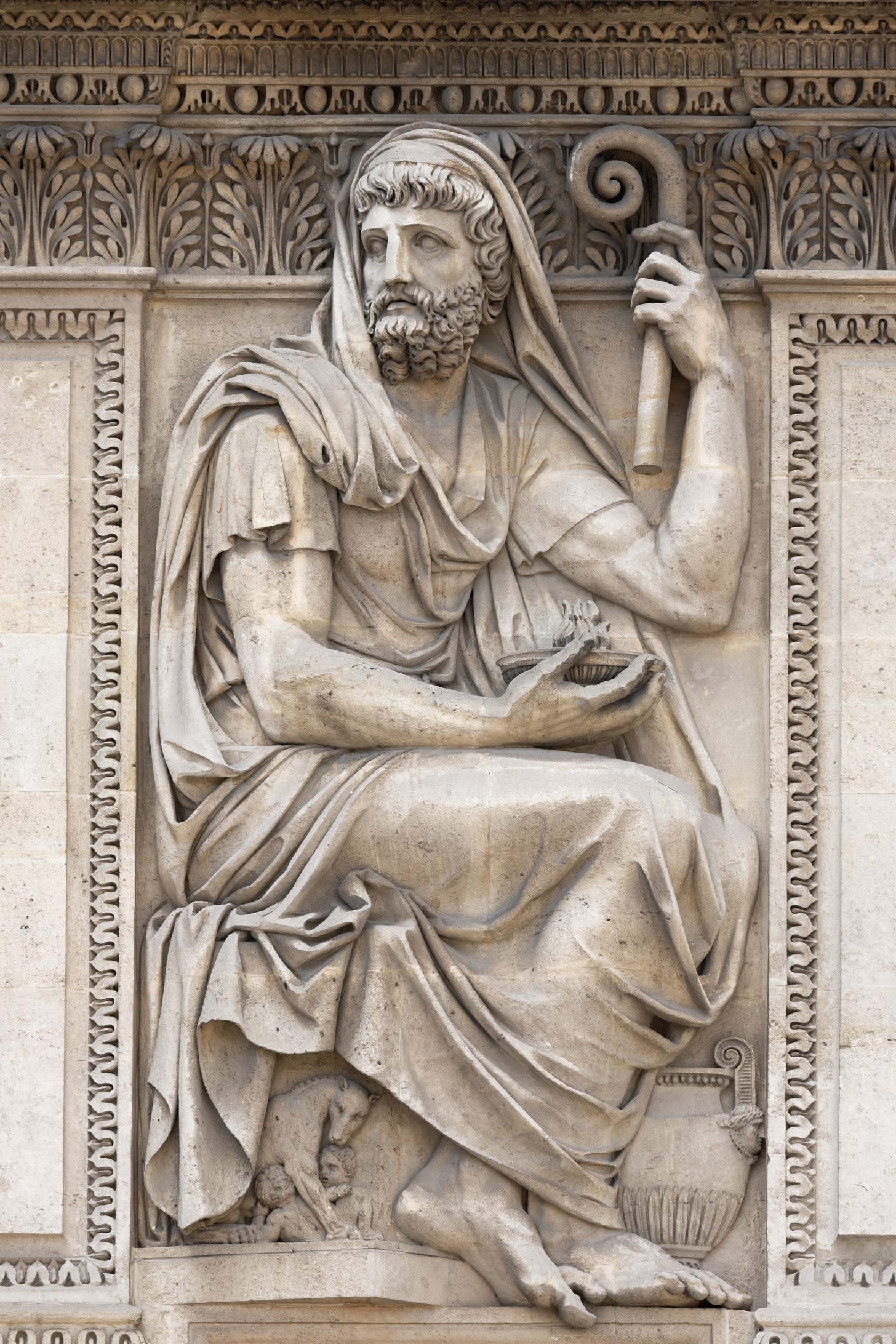

Lycurgus, whose image emerges from the shadows of legend, was known as the lawgiver of Sparta and may have been contemporary with Homer—which is to say, he may have lived circa 9th century BC. After briefly ruling as king of Sparta following his brother’s death, Lycurgus voluntarily relinquished the throne to a newborn nephew with a more direct claim. He then went abroad to study different cultures and governments in order to determine those which were most conducive to the happiness of a people. After some years, the citizens of Sparta recalled Lycurgus home to resume the throne, the incumbent child king having proven ineffective as a ruler (imagine that).

As king, Lycurgus instituted a number of laws and customs that effectively re-ordered the whole Spartan society, including:

Instituting a senate of 28 men to rule alongside the Spartan kings

Abolishing personal wealth and redistributing property in order to curb avarice

Replacing gold and silver currency with large iron discs that discouraged local commerce and virtually eliminated foreign trade

Instituting the common dining table and fraternity-like companies of young men for raising up warriors

Combining libertine marriage customs with authoritarian education in order to generate a hardy and duty-bound population to serve Sparta

Plutarch writes that the “whole course of [Spartan] education was one continued exercise of a ready and perfect obedience.”2 For Lycurgus believed that his people’s happiness depended most on the exercise of civic virtue, with individual rights and dignities being subordinated to the public good. (We might also mention that the majority of people living in Sparta at that time, i.e. the Helots, were slaves whose labor exploitation made possible the citizens’ enjoyment of leisure, discourse, and physical training.)

Numa Pompilius - Piety and peace

Plutarch contrasts the life of Lycurgus with that of Numa Pompilius, another quasi-legendary king of Roman lore. This story begins 37 years after’s Rome’s founding (circa 750 BC) when its mythical king Romulus mysteriously disappeared. During the ensuing interregnum, Rome’s two rival tribes—the Romans and the Sabines—laid aside their differences to elect a king acceptable to both factions. This man turned out to be Numa Pompilius, a private citizen of the Sabine tribe esteemed for his temperate and philosophic nature.

Numa was about 40 years old when Roman and Sabine ambassadors visited him in his quiet country retreat with the invitation to become their king. Much to the ambassadors’ surprise, Numa needed considerable persuasion to accept their offer. Once he did, however, he was greeted with joy and acclamation among the people. King Numa’s first order of business was to observe the royal investment ritual on Capitoline Hill in order to court the favor of the gods—a religious act that effectively established his agenda as King and High Priest (“Pontifex Maximus”).

Numa's kingship focused largely on performing frequent sacrifices and other sacred offices. As Pontifex Maximus, he was in charge of divine law, sacred rites, and providing for the care and conduct of the Vestal virgins, the consecrated women who maintained the city’s holy fire. It may seem odd to the modern reader that a king should be so concerned with the orthodox exercise of religion. Even Plato’s notion of kingship focused more on political than religious concerns. We should recall, however, that traditions going back to King Melchizedek in the Old Testament (Genesis 14:18–20) demonstrated the ancient unity of royal and priestly offices.

At the time Numa became ruler of Rome, the city had seen many years of wars and conflict. By turning the people’s attention to pious religious conduct, he ushered in a period of peace that endured for over four decades of his reign. Of the two priestly orders Numa instituted, the Fecials were invested with authority to negotiate diplomacy and war, demonstrating how closely Numa integrated the religious and political functions of his Roman government. Many even compared him to the acclaimed philosopher Pythgoras, as both figures maintained that "man's relations to the deity occupied a great place."3

The Two Kings Compared

After giving their individual stories, Plutarch sums up the similarities of Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius in one brief sentence:

Their points of likeness are obvious; their moderation, their religion, their capacity of government and discipline, their both deriving their laws and constitutions from the gods.4

He then enumerates their many points of difference in a sort of contest in which, arguably, no clear “winner” appears. Lycurgus had the harder task of enforcing economic equality on his people, but Numa was more humane. Under Numa’s rule, Rome demonstrated a democratic spirit, while under Lycurgus, Sparta maintained a rigid aristocracy. As to their enduring legacies, Plutarch notes that Lycurgus effectively “bred” his laws into his people, ensuring they would continue with little alteration for over 500 years; meanwhile Numa’s policy of “peace and good will,” so popular and successful during his reign, ended abruptly with his death.

In my mind, the most revealing comparison for readers today is seen in the domestic laws and customs each ruler fostered. Plutarch describes Spartan women as “bold and masculine…absolute mistresses to their houses,”5 in contrast to Roman women who were esteemed for their modesty and adherence to strict rules of conduct. Sparta’s libertine sexual code tolerated (and even encouraged) extramarital liaisons decoupled from the taboo of adultery. It coincided, however, with an authoritarian approach to child-rearing which effectively treated offspring as property of the state. In contrast, the rearing of Roman children was left to the discretion of parents. Here the alert reader may recognize a pattern seen with some frequency today: the imposition of strict (even autocratic) controls on certain social behaviors while others are allowed to become increasingly unregulated.

So which political approach is ultimately better for a society? Plutarch concludes his comparison by noting an historical paradox that may also interest or perplex us today: why did Rome ascend to political greatness after abandoning Numa’s peaceful policies while Spartan Greece notably declined after discarding Lycurga’s laws? “A question that will need a long answer,” Plutarch informs us, and one that must first define better as “riches, luxury, and dominion” or “security, gentleness, and justice.”6

It’s still an important question, is it not? If you haven’t done so already, check out Online Great Books, a community of intelligent readers who engage in thoughtful debate about the common good.

Plutarch, John Dryden, and Arthur Hugh Clough. 2001. Plutarch's Lives: The Dryden Translation. Vol. 1, p. xxviii. New York, NY: Modern Library.

Ibid, p. 67

Ibid, p. 87

Ibid, p. 101

Ibid, p. 104

Ibid, p. 106

Another stellar write-up.