Odysseus and Dante in the Underworld: The Poetics of Descent

Literary and theological dimensions of the hero's journey to the underworld.

Unlock the timeless wisdom of the West—join The Occidental Tourist for weekly free insights into the books and ideas that have shaped history, culture, and the human spirit!

“The way up and the way down are one and the same.” — Heraclitus, epigraph to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets

In my previous post on Homer, I explored the theme of mênis—Achilles' rage—which dominates The Iliad’s foreground and fuels its tragic action. The Odyssey, in contrast, is the epic of nostos: the hero's return. In this post, I want to reflect on a related motif found in both Homer and Dante, one of the most intriguing and enduring images in the ancient imagination: the nekyia (νέκυια), a journey to the underworld.

Literary critic Northrop Frye notes that the gods of the traditional epics act in a continuous present, influencing events by the immediacy of their will.1 To obtain knowledge of the future, however, the epic hero must typically travel to the kingdom of the dead. This descent to the lower world is never merely geographical; it is a descent into liminality, the domain of memory, prophecy, and otherworldly wisdom. For the questing hero, the underworld reveals mysteries that can only be obtained through a confrontation with death itself.

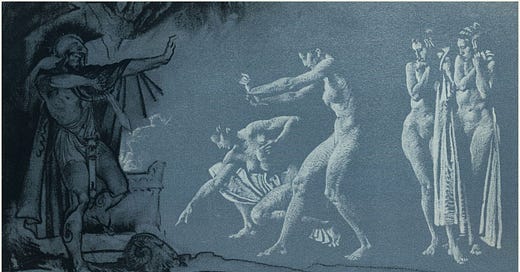

The nekyia in Homer’s Odyssey (Book 11) establishes the archetype. Odysseus, after an extended sojourn on Circe's enchanted isle, must travel to the underworld to consult the blind prophet Tiresias, whose counsel he needs to arrive safely in Ithaka and avoid rousing the already irate gods who oppose his nostos. Odysseus and his men depart Circe's island, sailing for the distant shore where Persephone’s black poplars hide the portal to the House of Death. There Odysseus performs a necromantic ritual: digging and filling a trench with libations of honey, milk, wine, and blood to summon the shades of the dead.

When Tiresias appears (whose name can be translated as "the weariness of rowing"),2 he instructs Odysseus on how to reach Ithaka and gives details of the impending showdown with his wife's suitors. But then the blind seer delivers an enigmatic prophecy: Odysseus must make a journey at the end of his life to a remote inland country, where he will plant his oar in the ground to appease Poseidon's wrath, concluding

And at last your own death will steal upon you...

a gentle, painless death, far from the sea it comes

to take you down, borne down with the years in ripe old age

with all your people there in blessed peace around you.3

After consulting with other shades, including his mother and fallen comrades, Achilles and Agamemnon, Odysseus returns to his ship by the same route and resumes his journey home.

Dante’s Descent

Other classical examples of nekyia include that of the Trojan hero Aeneas who goes down to Hades in Virgil's Aeneid. Dante Alighieri’s Inferno imitates Virgil’s thematic descent but transfigures it with history and Christian symbolism. Dante (the lost pilgrim) and his guide Virgil descend into the spiraling circles of Hell, which become successively more narrow as the horror of human dysfunction on display expands. Here, the architecture of Hell itself is a creation of divine justice whose sometimes mystifying penal logic Dante must assimilate before he can ascend again.

Unlike Odysseus, who returns to the upper world by the same route, Dante must pass through the lowest pit of Hell where Satan lies immobilized in ice, and there—by gravitational inversion—begin the long climb out the other side, emerging with Virgil's help at Mt. Purgatory. Dante’s path, then, is a reorientation: he comes out at the opposite end, having passed through the hellish depths of dysfunction. Before he leaves Hell, however, he encounters his famous forerunner, Odysseus, in one of the most memorable interviews of the Inferno (Canto 26).

The Dual Character of Ulysses

Traditions about Odysseus abound in Greek and Roman literature, with as many unflattering depictions as admiring ones. Even in Homer, wily Odysseus is never the purely virtuous hero. His character boasts of metis (cunning intelligence) marked by ambiguity. He succeeds by deception as often as by craft, usually blurring the boundary between them. In Dante’s Inferno, this ambiguity earns him condemnation. The poet places Ulysses (his Latin name) in the eighth circle of Hell among the fraudulent counselors, as punishment for his stratagems in the Trojan Horse affair and the theft of the Palladium, the sacred image of Athena.

The poet does not treat Ulysses simply with disdain, however. He raises him into a kind of tragic figure whose native nobility is undone by the same yearning that animates The Divine Comedy: the intense desire to know. Dante's Ulysses is consumed by an unbounded “lust for knowledge” that imitates our first parents' transgression.

Departing from Homer's storyline, this Ulysses tells Virgil and Dante how, after leaving Circe’s island with his men, he turned the ship’s bow westward toward uncharted seas, "making wings out of our oars in a wild flight"4 from the duties and consolations of home and family.5 Racing towards the other side of the globe, Ulysses spied mystical Mount Purgatory rising from the ocean, but a divine whirlwind caught the ship and sank it before they could approach the shore.

This recasting of the Odyssean myth is not simply poetic license. In Dante’s moral universe, Ulysses’ fate serves as a warning: unmoored from humility and the order of love, even the noblest yearning becomes destructive. This insight is intensified in Purgatorio 19, where the pilgrim is reminded that Ulysses embodied a specifically intellectual form of incontinence—gluttony for knowledge and experience.

Tennyson’s Ulysses: The Romantic Refashioning

Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s dramatic monologue “Ulysses” takes up Dante’s story and embellishes it with Romantic flair, embracing the hero's wanderlust as virtue. Written in 1833 while grieving the death of his friend Arthur Hallam (of “In Memoriam” fame), Tennyson’s poem portrays an aging and restless Ulysses at home, the burdens of kingship and domesticity weighing heavily on him: “I cannot rest from travel: I will drink / Life to the lees.”

This Ulysses feels the pinch of time. Scorning his quiet life in Ithaka and wearing his crown like a yoke, he aches to recover the vitality of youth. “How dull it is to pause, to make an end, / To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!” One's life, like a sword, must be continually tried in contests—not left to tarnish in disuse. And though diminished by age, Ulysses exalts the enduring spirit of man:

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are…

Rather than seeking wisdom from below or above, Tennyson’s Ulysses looks past the horizon. He dreams of sailing “beyond the sunset and the baths / Of all the western stars,” hoping to meet Achilles in the Happy Isles. Where Dante's Ulysses is punished for transgressing human bounds, Tennyson’s hero transforms that same longing into a defiant, noble hope: "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield."

His is not the way down, but the way out.

The Ultimate Descent: Christ’s Harrowing of Hell

Tennyson's "Ulysses" has rightly earned its laurels in literature as one of the great tributes to the human spirit, but it belies a modern conceit: that we can somehow leap towards infinite vistas of fulfillment by casting off the familiar ties that embed us in a particular place, family and community.

Between the ages of Homer and Dante, a new nekyia emerged in Western tradition that surpassed every other in heroic measure—its unlikely hero not resisting but yielding to the instrument of death…and paradoxically defeating it. Christians everywhere are observing it liturgically this week in the Paschal Mystery of the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, culminating in the Easter celebration.

The Church traditionally commemorates this nekyia on Holy Saturday. This event is known as the Harrowing of Hell, in which Christ descended to the dead following his crucifixion, to free the souls of the righteous awaiting their redemption. Its historicity is affirmed doctrinally in the Bible, but the imaginative details are elaborated in the Gospel of Nicodemus, an apocryphal text from the 4th or 5th century A.D. In this narrative, Christ breaks down the gates of Hades and liberates a host of saints from the Old Testament, including Adam, Abraham, and David. Dante preserves this story in Inferno 4, when Virgil recalls “a Great Lord” who entered Limbo and carried off many souls “making them blessed”.

Unlike Tennyson’s Ulysses, Christ does not flee from mortality but embraces it in obedience to his Father who ordained his death for the salvation of souls. The Catechism of the Catholic Church declares: “Christ went down into the depths of death so that ‘the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live’” (CCC §635). His descent is not an evasion of suffering but its transfiguration. By descending in obedience and ascending in triumph, Christ unites the “way down” with the “way up.”

Three Modes of Descent, Three Modes of Life

What emerges from this meditation on the nekyia are three archetypal paths of descent, each offering an ethical vision of the way down into finitude as the way up into liberation.

Odysseus’ descent is the path of gnosis. He enters the shadow world to learn hidden truths, reckon with death, and navigate his return. It is a ritual of memory and grief, undertaken for prophetic guidance.

Dante’s descent is the path of conversion. He goes down into Hell to confront sin and dysfunction so he can turn away from error and find his way back. He emerges not by his own heroism, but by grace and a guide.

Christ’s descent is the path of oblation. It is not self-seeking but self-emptying, a journey into the depths of God-forsakenness to offer oneself for the redemption of others.

Tennyson’s Ulysses, by contrast, rejects the nekyia altogether. Rather than adapt to the tragic level of existence—aging, suffering, finitude—he leaps into the unknown. It is a bold gesture against fate—Beethoven shaking his fist at heaven, if you will—but ultimately an ineffective escape from the vicissitudes of time. William F. Lynch, in Christ and Apollo, notes that the Romantic hero, like Tennyson’s Ulysses, “shut[s] himself off in solitude from man and God in order that he may stand brilliantly on his own.” But this leap toward infinity ends not in transcendence, but in a “tenuous, unreal dream that has no roots in the earth.”6

During this Holy Week, especially, it’s a good reminder that true transformation comes not by refusing the downward journey, but by embracing it. The nekyia teaches us that only by facing the reality of death, failure, and finitude with courage and patience, can we hope to rise—not as gods, but as redeemed and reoriented human beings.

Bonus Audio: “The Harrowing of Hell” read by Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick on The Lord of the Spirits podcast.7

Like many websites, The Occidental Tourist uses affiliate links, which allows us to earn a small commission on any qualified purchases, at no additional cost to the buyer.

Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957) 321.

Harold Bloom, ed., Homer’s The Odyssey, Bloom’s Guides (New York: Chelsea House Pub, 2007) 57.

Homer, The Odyssey, Book 11, lines 153-156, Robert Fagles translation (1996).

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Canto 26, line 125, Allen Mandelbaum’s translation (1980).

Don’t forget the prophecy of Tiresias that compelled Odysseus to plant his oar far from the sea, ending his wanderings and making peace of Poseidon. This quest westward is as much an act of impiety as it is a dereliction of duty to family and kingdom.

William F. Lynch and Glenn C. Arbery, Christ and Apollo: The Dimensions of the Literary Imagination (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2004) 111.

https://www.ancientfaith.com/podcasts/lordofspirits/the_harrowing_of_hell/