Homer, the Consummate Poet: An Introduction for Dante Readers

Discover why the ancient bard still speaks to us—and why Dante readers should listen.

Unlock the timeless wisdom of the West—join The Occidental Tourist for weekly free insights into the books and ideas that shaped history, culture, and the human spirit!

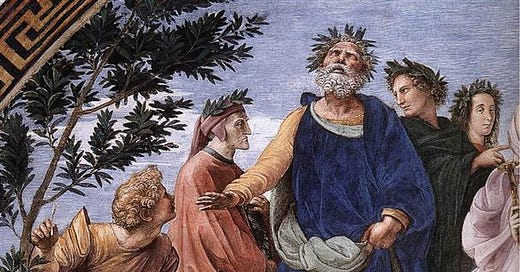

My kindly master then began by saying:

“Look well at him who holds that sword in hand

who moves before the other three as lord.

That shade is Homer, the consummate poet.”

Dante Alighieri, Inferno Canto 4, 85-88

It’s the season of Lent, a time for deep reflection, and I’ve been procrastinating on writing this post about Homer’s influence on Dante. I think I know why—how does one begin to write about the first and arguably most influential storyteller in the Western literary canon? I may as well pontificate on the Bible or Shakespeare. Certainly, whatever I have to say on the subject pales in comparison to the works themselves and the genius behind them. The old adage, "fools rush in where angels fear to tread," comes to mind.

That said, I've promised to bring you Homer, and I intend to deliver. As another saying about angels goes, they can fly because they take themselves lightly. Allow me then to proceed in that light-hearted spirit.

Why Read Homer? Why Read Homer for Dante?

Why is it important to read Homer in general, and as preparation for The Divine Comedy specifically? Author Adam Nicolson takes up the first part of this question in Why Homer Matters: A History. As the foundation myths of Greek culture, the Homeric epics have formed the imaginative backdrop of the Western collective consciousness for more than three millennia. The Iliad and The Odyssey—including the oral tradition that predated their transition to written form—help fill what Nicolson calls "a third space" between our own cultural memory and a distant mythic past that predates the historical record. In other words, Homer reveals to us how we became who we are.

Inquire, please, of the former age, and consider the things discovered by their fathers; for we were born yesterday, and know nothing, because our days on earth are a shadow.

Job 8:8-9 NKJV

Homer was not a direct influence on Dante, who did not know Greek at a time when the ancient poet’s works were unavailable in Latin. It is accurate to say, however, that Dante cherished a deep affection for Homer, having encountered him concomitantly in other writers.1 Certain key figures (foremost of whom are Achilles and Odysseus) appear in the The Divine Comedy, but Dante absorbed them through Roman and medieval sources rather than from Homer’s own words.

Even so, we want to be familiar with Homer as we read Dante because he forms the bedrock of Western literature and, in that sense, was a natural part of Dante's literary formation. Most significantly, Dante’s greatest inspiration, the Roman poet Virgil, consciously assimilated the Homeric legacy in what is perhaps the world’s most acclaimed piece of fan fiction, The Aeneid—thus making Homer an inescapable presence in The Divine Comedy.

But I think both of these considerations fall short of a still larger reason why reading Homer remains a meaningful undertaking today, which is to say, Homer makes us more human.

Homer and the Human Experience

The intellectual disciplines collectively called the Humanities are so named because they humanize us. Blaise Pascal famously wrote that “man is neither angel nor beast."2 I would add that he is not a machine either—though modernity since Descartes (Pascal’s contemporary), has often reached for mechanistic metaphors when describing him. Man is not an angel, though he possesses intellect and reason, and he is not a brute animal, though he possesses bodily needs and instincts. He is a unique, living composite, standing upright between heaven and earth, a microcosm of all reality.

This is what we see in Homer: epic stories that span the full range of human experience, from earthly and mortal struggles to numinous and divine encounters. One of my favorite examples of this is The Shield of Achilles in The Iliad, Book 18. Achilles, grieving the loss of his closest companion, Patroclus, requires new armor to avenge his friend’s death. His shield, forged by the blacksmith god Hephaestus, becomes a microcosm of human society—depicting not just war and conflict, but also peace, celebration, and daily life. Even with its mythic elements, Homer delivers a profound and truthful vision of the human condition.

How to Read Homer

Since I’ve mentioned the gods, let me briefly address how to approach them literarily, without the discomfort that modern retellings often provoke. Yes, Homer deals in myth—that is, his stories belong to the realm of archetypes, the original patterns that have shaped storytelling across the ages. You don’t read a myth the way you read a realistic novel. These stories don’t lose their power because we no longer believe in Homer’s pantheon. Rather, we lose something when we fail to recognize that myths are not naive make-believe but works of exquisite imagination containing truths too dense for mere historical facts.

The best way to read Homer, then, is to let the myths work on you at a deep, subterranean level—by simply enjoying them on their own enchanted terms.

Resources for New Readers

If you’re encountering Homer for the first time, I recommend heading over to the Substack newsletter Beyond the Bookshelf by fellow Navy veteran Matthew Long. His post, An Introduction to the Iliad, is ideal for new readers or those who want to be reacquainted with Homer. If you subscribe now, it’s not too late to follow along in real time with his Iliad reading plan and Deep Reads Book Club discussions.

Most new readers, of course, will ask which translation to use. The best translation, in my opinion, is the one you already own. However, if Homer is not yet on your bookshelf, I’m partial to Robert Fagles’ translations. Published in the 1990s, these editions have become popular staples in classrooms and reading groups because they balance poetic form with vivid contemporary style. Every translation involves trade-offs, but Fagles’ version is both faithful and accessible.

For first-time readers, my advice is: don’t get bogged down by the vastness of Homer’s epics. I don’t know how many distinct characters each work mentions, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it numbered in the hundreds. Many of these names appear only once, often in reference to their gory deaths on the battlefield. Focus on the main characters and storylines—Achilles, Odysseus, Agamemnon, Hector, Priam, Paris, Helen, Penelope, and Telemachus among others—and let the rest flow around you. It’s okay to approach your first reading mainly as an introduction to the story and Homer’s narrative style. If you are truly committed to crafting a literary life shaped by the imaginative vision of the great masters, you will return again and again to these epics, with each experience deepening your understanding and appreciation.

By the way, if you’re inclined toward audiobooks, I highly recommend them as a first or subsequent read since Homer’s poems were, after all, originally recited aloud. Audible offers an excellent abridged narration of Fagles’ Iliad, with the unabridged version coming out this summer. If my memory serves me correctly, I enjoyed this version during my very first reading of Homer over 10 years ago.

Finally, unlike great novels, myths do not lose their imaginative power when they are adapted or abridged to make them more approachable. For a charming adaptation of the Greek myths—including Homer’s stories and themes—I recommend Edith Hamilton’s Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes (the 75th Anniversary edition is lovely!) Check out specifically Part Four, The Heroes of the Trojan War. It covers key events from The Judgment of Paris (which, while not included in The Iliad, was part of the broader mythic tradition) to the fall of Troy, the post-war wanderings of Odysseus, and even Aeneas’ Virgilian quest for a new homeland.

I hope this inspires you to read a little Homer this month. In future posts, I’ll explore the key figures of Achilles and Odysseus; the themes of rage and wandering; and the role of Homeric epithets and similes. Post your comments or questions below.

Happy Reading!

Please note, as an Amazon affiliate, I can earn a small commission on qualified purchases through links in this post, at no additional cost to the buyer.

Cf Dué C, Lupack S, Lamberton R. Dante and Homer. In: Pache CO, ed. The Cambridge Guide to Homer. Cambridge University Press; 2020:582-584.

Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 358.

Amy, if I were counseling someone partaking of a first read of the Iliad, or even a grizzled veteran of many readings, I would strongly recommend turning to Simone Weil’s essay, “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force.” I’m sure you’re familiar with it, but for other readers, she identifies force (”all is settled with the coercion of force”) as the center of the Iliad. You said “Even with its mythic elements Homer delivers a profound and truthful vision of the human condition.” Yes he does, and in the Iliad it is dark indeed. Weil said “The Iliad is the purest and loveliest of mirrors.” If it is, it’s as dark as the Aztecs’ Tezcatlipōca (“smoking mirror,” referring to the obsidian mirrors used by the Aztecs, who, it goes without saying, were familiar with “coercion by force.”)

Simplistic renderings often treat the Iliad as a heroic saga, but it is — at its core — a seesaw of retribution. It reminds me of Voltaire’s gibe: “I know I am among civilized men because they are fighting so savagely.” And, unlike the Commedia, the Iliad only provides literary glory and immortality; there is no consoling prospect of the glory and immortality of the Empyrean. That said, there are so many deep familiarities — expressions of vindictiveness and cruelty interspersed with tenderness and pity. Both offer profound treatments of love, justice, courage and yes, wrath. The antagonists in the Iliad are active participants in war’s cruel and absurd contradictions, and Dante, likewise, is an active participant in Hell’s.

Lest I leave the impression I read the Iliad as nonstop Thunderdome (I don’t), I was particularly taken by what Weil describes as “the friendship that floods the hearts of mortal enemies.” She describes it as the purest triumph of love, the crowning grace of war; “the distance between victor and vanquished shrinks to nothing.” Achilles and Priam have such an exchange. Dante’s tender interaction in Canto V of Purgatorio with my favorite character in the Commedia, his former foe Bonconte I da Montefeltro, is a case in point.

These epics depict two great human struggles: one of force, and one of faith. Weil notes “The Gospels are the last marvelous expression of Greek genius, the Iliad is the first.” The Gospels and epics are, to me, waves continuously shaping humanity’s coastline. Psalm 144:4 says, “Man is like a breath; his days are a passing shadow.” But during that breath, we can experience almost 3,000 years of genius and the profound impact of those waves. What a blessing.