Medieval Eggs of Jesus: Unlocking the Four Senses of Scripture

An adventure in literary interpretation, Part II.

Unlock the timeless wisdom of the West—join The Occidental Tourist for weekly free insights into the books and ideas that have shaped history, culture, and the human spirit!

Last week, I wrote about the curious reference in the lectionary readings for the 3rd Sunday of Lent to a “spiritual rock” that followed Moses and the Israelites during their desert wanderings. According to St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 10:4, “the rock was Christ.” It’s a concise Christian interpretation but it left me wondering: what is the full story behind this mysterious rock, and how ought we to understand Paul’s claim today?

In this post, I’ll share what I’ve since discovered about Moses’ miraculous rock and offer you some interpretive tools to unlock not only the full meaning of this passage, but also the symbolic language of many great works of imaginative literature. To do so, we’ll turn to the fourfold method of medieval exegesis—hilariously rendered by my phone’s voice-to-text feature as “medieval eggs of Jesus”. 😂

Rock of Moses, Part Deux

This week, I immersed myself in rabbinic interpretations of the events at Horeb, where water sprang—twice—from an ordinary rock, according to the biblical accounts in Exodus 17 and Numbers 20. While the Jewish Midrash offers various interpretations, the basic storyline is this: God provided the Israelites with a miraculous source of water from a rock struck by Moses at the beginning of their desert exile. This source sustained them throughout their forty years of wandering1 and came to be known as “Miriam’s Well”, flowing, it was said, on account of the goodness of Moses’ sister Miriam until her death in the fortieth year.2

With Miriam’s passing, the water dried up—which is subtly suggested by the sequence of events in Numbers 20:1-2—and once more the people quarreled with Moses. Entreating God to intervene, Moses received divine instruction to speak to the rock. This is where the rabbinic commentary becomes somewhat muddled: apparently, the original rock rolled away and concealed itself (!) among the other boulders.3 Moses attempted to address it but—whether through a case of mistaken rock identity or a lapse in pious trust—he failed to produce water. In frustration, he struck the rock twice. This time water flowed, but Moses’ disobedience triggered God’s displeasure and a hefty penalty: he was barred from entering the Promised Land.

Unlocking the Meaning of the Text

This rich and layered story, spanning two great religious traditions, beguiles us with its interpretive possibilities. How should modern readers understand the ancient narrative, presented as part miracle, part mystery, part moral reckoning? If we resist the reflexive and, frankly, pedestrian urge to dismiss it as a tall tale or nursery story, we are still left with several hermeneutic options. Is it merely a historical account? A moral lesson? A veiled prophecy? Or something more transcendent altogether?

To approach such questions with theological and literary depth, I sought a method capable of attending to all these dimensions at once. In a flash of inspiration, I remembered William F. Lynch’s Christ and Apollo: The Dimensions of the Literary Imagination (1960). I first read this work of literary criticism for a graduate course in Literary Theory nearly a decade ago. Grabbing it from my bookshelf, I opened it at random to the supplement on “The Fourfold Method of Exegesis”.

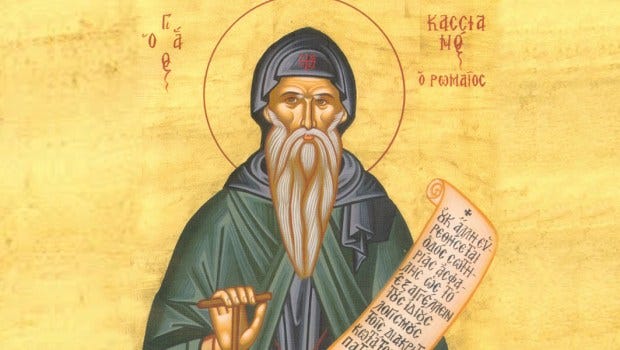

In the section quoting theologian John Cassian (ca. 370-435), I read:

Surely revelation refers to allegory through which those things that historical narration touches upon are revealed in a spiritual sense and meaning. It is as though we tried to explain how “our fathers were all under the cloud and all in Moses were baptized”…and “all did eat the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink of the rock that followed them4; and the rock was Christ” (1 Corinthians 10:1-4).

Bingo! Here was the precise interpretive key I needed in the work of a venerable theologian tackling the selfsame passage in question more than a millennium and a half earlier. Nihil novi sub sole.5 I need only take my hermeneutic cues from the exegetical method he was expounding and apply it to my reading of the text today.

Littera gesta docet, quae credas Allegoria,

Moralis quid agas, quo tendas Anagogia.

The Literal teaches deeds, what to believe is Allegory,

The Moral is what to do, what to aim for is Anagogy.

Nicholas of Lyre, 14th century

Layers of Meaning: A Journey Through Sacred Imagination

Central to medieval exegesis, which originated in the Patristic period and reached its peak in the Middle Ages, is its fourfold sense of Scripture: a way of reading that opens up the text on four levels of meaning, identified as literal (or historical), allegorical, moral, and anagogical. Far from being a relic of the past, this method remains a powerful tool not only for understanding Scripture but for interpreting the symbolic structure of much of Western literature.

So let’s take a closer look at how medieval exegesis works, and how we can use it to illuminate both the rock in the wilderness and the Rock “who followed them”. We’ll start by unpacking each interpretive layer as a progressively unfolding encounter with meaning.

Literal: The literal or historical meaning is the basis for all figurative interpretations, according to the 12th-century theologian Hugh of St. Victor. It refers to the ordinary sense of the words or story taken at face value.

Allegorical: Allegory is the spiritual sense “signified [when] the letter of Scripture symbolizes, in turn, another fact, present or future.”6 Traditionally, the events of the Old Testament are understood as figures of the New—frequently as types or manifestations concerning Christ or the Church.

Moral: This is also called the tropological sense (think: tropes). It is the moral or ethical meaning that arises from the figurative sense of the text. Typically, this sense refers back to Christ whose example impels us to reform our own actions.

Anagogical: The Greek word anagoge means “to lead up”, to ascend. Thus, this sense refers to the final or eschatological fulfillment of the previous senses—the glorious or heavenly destiny to which they all point in Christ.

As was his wont, St. Thomas Aquinas adds a systematic approach to this method. First, he says, it’s not the case that every passage contains all four senses. Everything written has a literal sense, of course, but not all passages carry every spiritual meaning. Furthermore, where spiritual meaning is concerned the reader must begin with a thorough understanding of the text’s literal sense. You cannot just apply any spiritual sense, which is not grounded in the literal meaning.

Subsequently, the symbolism of Christ present in the allegorical sense is meant to illuminate his mystical Body, the Church, while the moral sense applies the example of his life to the conduct of the individual believer. Finally, Thomas warns, nothing in Scripture is expressed in hidden meaning which is not clearly explained elsewhere. “Thus a spiritual interpretation should always be supported by some literal interpretation of Holy Scripture” to avoid any occasion of error.7

Understanding “The Rock That Was Christ”

Now we are ready to apply our interpretive prowess to St. Paul’s passage in 1 Cor 10:1-4:

I do not want you to be unaware, brothers and sisters, that our ancestors were all under the cloud and all passed through the sea, and all of them were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea. All ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink, for they drank from a spiritual rock that followed them, and the rock was the Christ. (1 Cor 10:1-5)

This passage spells out the allegorical sense of the Old Testament stories of the rock at Horeb in Exodus 17 and Numbers 20. Paul attests to the rabbinic tradition that the rock (or the water) followed the Israelites during their sojourn. By concluding that the rock was Christ, he is pointing to the sacramental meaning behind the miracles of the Hebrew Exodus: baptism and the Eucharist, specified as “spiritual food” (symbolized by manna) and “spiritual drink” (symbolized by water).

The element of water, too, is rich with allegorical meaning, prompting us to recall the “living water” mentioned in such passages as John 4:10 (the “Woman at the Well”), John 7:37-38 (“rivers of living water”), and Ezekiel 47:1-12 (“I saw water flowing from the temple”). According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), water is a symbol of the Holy Spirit, not only in baptism but also in our souls: “Thus the Spirit is also personally the living water welling up from Christ crucified as its source8 and welling up in us to eternal life.”9

This image now calls forth the moral meaning for each believer. It includes an invitation to mental prayer, “the encounter of God’s thirst with ours.”10

The Holy Spirit is the living water “welling up to eternal life” in the heart that prays. It is he who teaches us to accept it at its source: Christ. Indeed, in the Christian life there are several wellsprings where Christ awaits us to enable us to drink of the Holy Spirit (CCC #2652).

These include the Word of God, the Liturgy of the Church, the theological virtues, and the sacramental mystery of the present moment (“If today you hear his voice…”).

Finally, the anagogical mystery prefigured by Miriam’s Well and the Rock of Christ points to the “river of life” flowing from the Throne of God and the Lamb in the New Jerusalem (Rev. 22:1). With this beautiful, Spirit-filled vision of the heavenly kingdom, the whole dramatic arc of salvation history is brought to its joyous completion…as is this very long post. Thank you for reading!

Like many websites, The Occidental Tourist uses affiliate links, which allows us to earn a small commission on any qualified purchases, at no additional cost to the buyer.

Cf Midrash Tanchuma, Chukat 20 and 21.

“The well was given to the Jewish people in the merit of Miriam; the pillar of cloud was in the merit of Aaron; and the manna in the merit of Moses. When Miriam died the well disappeared, as it is stated: ‘And Miriam died there’ (Numbers 20:1), and it says thereafter in the next verse: ‘And there was no water for the congregation’ (Numbers 20:2). But the well returned in the merit of both Moses and Aaron.” Taanit 9a.

Shlomo Chaim Kesselman, “Moses Strikes the Rock: The Full Story,” accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3839434/jewish/Moses-Strikes-the-Rock-The-Full-Story.htm.

William F. Lynch and Glenn C. Arbery, Christ and Apollo: The Dimensions of the Literary Imagination (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2004), 306. Emphasis mine.

“Nothing new under the sun.” Cf Ecclesiastes 1:9.

Lynch, Christ and Apollo, 310.

Ibid, 314.

We should specifically recall the soldier piercing Christ’s side with a lance during his Crucifixion, in which blood and water flowed from the wound. See John 19:34.

CCC #694.

CCC #2560.